I am an abstract painter. I do not usually paint to "re-present" existing people or objects. I believe that works of art, or works in a series, are not imitations, or tricks, and should not simply stand in for another (worthier) object, the painting of the golden bowl a simple study in skill. The painting is, itself, the thing.

My husband and I, who generally agree on things artistic, have these discussions. I have always thought that art should be about "something," that there must be a subject matter; most of my painting heroes argue along these same lines: Motherwell created the Spanish Civil War series, and Agnes Martin, the "perfect space." Painters like Helen Frankenthaler and Joan Mitchell have been too easily dismissed because critics said that their work was not about anything, that it was too lyrical, too beautiful.... A shudder dismisses the work and then passes through all of us. We all approach the studio with an idea, I believe.

But Charley says that art can be, simply, beautiful, gestural, with no "three o'clock on a Tuesday afternoon in Taos," even in an abstract vein, about it. Rothko, he says, may have believed that certain of his works were violent, but it would be difficult to convince viewers -- who see the colors floating on the canvas -- to find that same intended violence. Art is about the way the piece itself meets its viewer, ultimately. And Charley has some pretty impressive artists who would appear to be on his side; isn't Pollock's work largely "about" the painting itself? Picasso was loathe to release the work from his studio because then it was out of his control. And Bruce Nauman wrote somewhere that "whatever I was doing in the studio must be art." (That's WHATEVER, equalling art).

So, today, when I was reading in Mirror of the World: A New History of Art, by Julian Bell (New York: Thames and Hudson, 2010) I saw this amazing photograph of two paired screens by Ogata Korin, called "Red and White Plum Trees," from about 1712. Bell writes that the artist, here, "touches on ancient themes of seasonal transience and complementary opposites" but also "cancels them out flamboyantly." The work's "dazzling flatness seems to declare that painting can simply be decorative, simply a demonstration of exquisite taste and perfect poise without further significance. At least, such was the rhetoric that gathered around its painter. Korin himself was a dashing bourgeois dilettante...." (265). Here is a photo of the work:

So I would say, the painter is delineating the tree branches perfectly (what Bell refers to as demonstrating "seasonal opulence"), yet he then gives us a pattern, in what seems to be an anticipation of Klimt, to show us the flow of the river, then he allows an entirely abstracted gold-leaf ground to stand ... itself signifying "nothing." So we have the full movement from representation to abstraction, from intentional rule and role-playing to throwing over all the rules.

Charley and I would agree, I suspect, that the gold here is the stunner. The complete expanse of (Nauman's) "whatever" takes the breath away. But... there's still that about/not about thing....

So then Bell talks about Dong Qichang, from China. Dong had argued that a painter named Ni Zan, who painted, he said, "merely to sketch the exceptional exhilaration in my breast" (139) could be seen as perfectly right in his (oh-so-loosely-representational) idealism, which, Bell writes, meant that Ni Zan, in Dong's theory, "kept a judicious, culturally well-informed distance from the crude imprint of the immediately visible" (266). I love that sentence of Bell's. Wow. The "crude imprint of the the immediately visible." It's pretty tempting to leap right into that, but I can't, really.

I think it takes a lot for an artist to to get the viewer to the "immediately visible." And I think it means that yes, that "visible" stuff can be pretty, or violent, or "nothing." But there still, for me, is a subject matter, even if that subject matter is "the crude imprint," the subject matter being, itself, the subject. "How to paint this" is, to me, a huge subject to articulate on canvas. But we will talk more....

Tuesday, May 31, 2011

Sunday, May 29, 2011

Maybe it was Pratt, Kansas?

Somewhere in the middle of Kansas, the world changes, from the West to the East, from dry to wet, from brown to green, from sparsely forested to trees reclaiming farm fields...

the change, in a sketch....

the change, in a sketch....

Friday, May 27, 2011

"I am not fine -- nothing fine about me...

And I'm not sorry about it either. I'm only what I am -- and I'm free to live the minutes as they come to me -- if you know me at all you must know me as I am. The night is very still." (from Roxana Robinson's "Life," p. 185).

This is Georgia O'Keeffe at her best: honest, feisty, serious. I love this about her. The Georgia O'Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, New Mexico is currently showing only a few of her works, including a gorgeous painting that I had never seen before, called "A Street," from 1926. The painting doesn't portray the street at all, only the sky between two skyscrapers, with a streetlight one of the only clues to the realism of the work. The museum labels quote O'Keeffe as saying that she noticed that, as taller and taller city buildings were constructed, people looked at them, because they were so large. She said she thought that she could perhaps allow people to see flowers with the same attention if she made them large, as well. And they did start looking, she said.

Many O'Keeffe works are in storage at the moment, as the museum is given over to the show called "Shared Intelligence: Painting and the Photograph." David Hockney, a Chuck Close, Sherrie Levine... good, good art. One painter, Audrey Flack, juxtaposes faces from a source photograph by Margaret Bourke-White; the faces are the people liberated from Buchenwald in 1945, and Flack's additions, brightly-painted material goods (pearls, a silver candlestick, petit-fours) are even more emotionally jarring than Bourke-White's photograph, I think. The curators point out that many painters have used photographs as their sources but that only some, like Flack, mention this. The show puts together two photographs by Thomas Eakins, one of a tree and one of two men, and the painting "Mending the Net" from 1881. Eakins, the curators say, projected photographs onto canvas and traced them. But told no-one. This photograph comes from the show's brochure... just look at the similarities:

The show also has a copy of David Hockney's Secret Knowledge on display -- the use of lenses, Hockney argues, shows up earlier and more universally than anyone had previously argued. Fabulous book and very compelling theory. This show should be seen. It is fine.

This is Georgia O'Keeffe at her best: honest, feisty, serious. I love this about her. The Georgia O'Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, New Mexico is currently showing only a few of her works, including a gorgeous painting that I had never seen before, called "A Street," from 1926. The painting doesn't portray the street at all, only the sky between two skyscrapers, with a streetlight one of the only clues to the realism of the work. The museum labels quote O'Keeffe as saying that she noticed that, as taller and taller city buildings were constructed, people looked at them, because they were so large. She said she thought that she could perhaps allow people to see flowers with the same attention if she made them large, as well. And they did start looking, she said.

Many O'Keeffe works are in storage at the moment, as the museum is given over to the show called "Shared Intelligence: Painting and the Photograph." David Hockney, a Chuck Close, Sherrie Levine... good, good art. One painter, Audrey Flack, juxtaposes faces from a source photograph by Margaret Bourke-White; the faces are the people liberated from Buchenwald in 1945, and Flack's additions, brightly-painted material goods (pearls, a silver candlestick, petit-fours) are even more emotionally jarring than Bourke-White's photograph, I think. The curators point out that many painters have used photographs as their sources but that only some, like Flack, mention this. The show puts together two photographs by Thomas Eakins, one of a tree and one of two men, and the painting "Mending the Net" from 1881. Eakins, the curators say, projected photographs onto canvas and traced them. But told no-one. This photograph comes from the show's brochure... just look at the similarities:

The show also has a copy of David Hockney's Secret Knowledge on display -- the use of lenses, Hockney argues, shows up earlier and more universally than anyone had previously argued. Fabulous book and very compelling theory. This show should be seen. It is fine.

Thursday, May 26, 2011

"... the difference between things..."

"I don't paint things; I only paint the difference between things." --Henri Matisse

The "difference between" got me thinking about two kinds of worlds:

--the horizon. We can see it, we can change its appearance as we walk towards it or away from it, but it always seems to be a defining line, the curve we are heading for... we didn't create it. But it is something we can claim to "see" and paint as the defining line "between" earth and sky...

--the (artistic) borders we create, that make one surface seems different than another, "between things"

A mirror, complete with a beaten metal and tiled border, in Taos, above and:

a sketch of borders and horizons and a small explosion...

The "difference between" got me thinking about two kinds of worlds:

--the horizon. We can see it, we can change its appearance as we walk towards it or away from it, but it always seems to be a defining line, the curve we are heading for... we didn't create it. But it is something we can claim to "see" and paint as the defining line "between" earth and sky...

--the (artistic) borders we create, that make one surface seems different than another, "between things"

A mirror, complete with a beaten metal and tiled border, in Taos, above and:

a sketch of borders and horizons and a small explosion...

Wednesday, May 25, 2011

"... a perfect space"

If yesterday was hard and soft, today is about the way the object reaches into its space. Take a Taos, New Mexico doorway, for example, which is the object but also changes the light around it:

See how the door breaks into the outdoors, the flowers come towards us, the colors come away from the adobe finish...

Now take a detail of my sketch of a Southwestern rock formation, a vase, nearly, with a tree growing against one curved side:

Again, it's an object in outline, but because it doesn't fit our idea of "rock," we see the space around it more clearly...

Now, last, an Agnes Martin drawing. She has said, "I'm not trying to describe anything. I'm looking for a perfect space." She does not have the object-and-surrounding-space distinction. We saw her specially-constructed gallery of paintings at the Harwood Museum of Art in Taos... she gave them the seven works in the 1990's, and while she lived, often came to sit and look at them. The space is really wonderful. She found her perfect space, both within each painting and here, in the gallery, around them all. I don't have any photographs of those works, but I do have a photograph of a small reproduction of a Martin drawing from the same period (the photograph was taken with my camera -- the pen is there for scale --from the exhibition catalogue, along with the above quote, from Agnes Martin, Richard Tuttle, ed. Michael Auping, 1998: Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Texas):

You can't see an Agnes Martin -- not really -- unless you are standing in front of it. She doesn't reproduce well. There aren't many catalogues in existence. It's a rare thing, her work. There are painitngs of hers in the Tate, in the Metropolitan Museum in NYC, at SFMOMA ... those are the ones I know about. Go and see her stuff. Come to Taos and see this room. She's amazing.

See how the door breaks into the outdoors, the flowers come towards us, the colors come away from the adobe finish...

Now take a detail of my sketch of a Southwestern rock formation, a vase, nearly, with a tree growing against one curved side:

Again, it's an object in outline, but because it doesn't fit our idea of "rock," we see the space around it more clearly...

Now, last, an Agnes Martin drawing. She has said, "I'm not trying to describe anything. I'm looking for a perfect space." She does not have the object-and-surrounding-space distinction. We saw her specially-constructed gallery of paintings at the Harwood Museum of Art in Taos... she gave them the seven works in the 1990's, and while she lived, often came to sit and look at them. The space is really wonderful. She found her perfect space, both within each painting and here, in the gallery, around them all. I don't have any photographs of those works, but I do have a photograph of a small reproduction of a Martin drawing from the same period (the photograph was taken with my camera -- the pen is there for scale --from the exhibition catalogue, along with the above quote, from Agnes Martin, Richard Tuttle, ed. Michael Auping, 1998: Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Texas):

You can't see an Agnes Martin -- not really -- unless you are standing in front of it. She doesn't reproduce well. There aren't many catalogues in existence. It's a rare thing, her work. There are painitngs of hers in the Tate, in the Metropolitan Museum in NYC, at SFMOMA ... those are the ones I know about. Go and see her stuff. Come to Taos and see this room. She's amazing.

Tuesday, May 24, 2011

entre l'arbre et l'ecorce il ne faut pas mettre le doigt...

In French, this means "between the tree and the bark do not put a finger" or, we would say, between a rock and a hard place... Today feels like a day to play with hard and soft... First, hard, the hardness of rock in the Canyon de Chelly, Arizona:

My friend used to have a sign over her desk that read "Go to the HARD place first"; she meant to remind herself that when she was working through a serious problem with a student (a problem the student might not want to face) words that needed saying had to be said ... first. Then everything else would come. These rocks look as though they have faded in the sun, almost like spread-out linen; so soft-looking, and yet... we will go second, then, to the sky above these same rocks:

Rocks and clouds take any shape...

My friend used to have a sign over her desk that read "Go to the HARD place first"; she meant to remind herself that when she was working through a serious problem with a student (a problem the student might not want to face) words that needed saying had to be said ... first. Then everything else would come. These rocks look as though they have faded in the sun, almost like spread-out linen; so soft-looking, and yet... we will go second, then, to the sky above these same rocks:

Rocks and clouds take any shape...

Monday, May 23, 2011

The Last New Picasso...

You will know by now all about the newest San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) show, called The Steins Collect: Matisse, Picasso, and the Parisian Avant-Garde. I quoted from the catalogue yesterday, which I now have and am slowly looking through ... the show is wonderful. It begins here and moves to Paris and New York. There are drawings, paintings, pieces of furniture, letters, plans by Le Corbusier, photographs and the collections are gathered together in the museum as they were acquired and displayed in each home ... this will not be happening again! The show helps explain the way the Steins' purchases and salons helped encourage the understanding and reputation of the newest wok of the twentieth century. Do go if you possibly can!

Gertrude Stein was able to purchase Picasso's work through the first World War, but his prices soon escalated and her final purchase, in late winter 1923, may have involved the exchange of an older Picasso. It is a still life now owned by The Art Institute of Chicago. In an attempt to see how this "final" Picasso was composed, I sketched it ... my version has some adjustments, made as I was reconciling my angles with Picasso's. The painting feels to me less like a collection of objects on a table, which it must be, given its title, than a nude or pair of lovers... and that would fit with one of the interesting discoveries we made while looking at the show: the Steins were exceedingly fond of nudes. Here is my version:

(Details, provenance and the reproduction published in the exhibition catalogue, pages 229 and 434)

Gertrude Stein was able to purchase Picasso's work through the first World War, but his prices soon escalated and her final purchase, in late winter 1923, may have involved the exchange of an older Picasso. It is a still life now owned by The Art Institute of Chicago. In an attempt to see how this "final" Picasso was composed, I sketched it ... my version has some adjustments, made as I was reconciling my angles with Picasso's. The painting feels to me less like a collection of objects on a table, which it must be, given its title, than a nude or pair of lovers... and that would fit with one of the interesting discoveries we made while looking at the show: the Steins were exceedingly fond of nudes. Here is my version:

(Details, provenance and the reproduction published in the exhibition catalogue, pages 229 and 434)

Sunday, May 22, 2011

Leo had Cezanne, Gertrude Picasso... one apple for five!

When Leo Stein left Rue du Fleurus, he and his sister Gertrude had to choose the pieces each wished to keep from their joint collection. Gertrude kept most of the Cubist works, and the Picassos, and Leo the Matisses and some of the older works. But they both loved the Cezanne sketch, "Five Apples." Leo prevailed, saying "The Cezanne apples have a unique importance to me that nothing can replace.... I'm afraid you'll have to look upon the loss of the apples as as act of God." Gertrude was not without resources, however, and when Picasso learned of the story, he painted Gertrude and Alice a replacement apple, and gave it to them for Christmas 1914. (Recounted in The Steins Collect, edited byJanet Bishop, Cecile Debray, and Rebecca Rainbow, SFMOMA and Yale University Press: 2011, p. 97).

Here is a sketch of a sketch of a sketch....

Here is a sketch of a sketch of a sketch....

Saturday, May 21, 2011

The Queen's Skirt Explodes, part II, this time with Bronzino's help

In a post on May 5th, I had written about the way that some portraits seems to privilege the satins and silks and ermines and jewels of their owners over... their faces, and I had given you a photograph of a painting from my series exploring the peculiarities of that subject...

And I have found a new painter who seduces with his brushed fabrics. Agnolo Bronzino, an extraordinarily talented Renaissance painter, lesser known than some of his contemporaries, has had two exhibitions devoted to him in the past year, one at the Palazzo Strozzi in Florence last winter and the other at the Metropoitan Museum of Art in new York last winter and spring. The catalogues are out, and there is a review by the very perceptive Ingrid Rowland in The New York Review of Books from May 26 (pages 8-10). It is a wonderful, thorough review; read it... it is really fine. She outlines the way he worked, his basing of some works on Michaelangelo's (and she reproduces a drawing as proof of this sculptural echo), and Cosimo de' Medici's choice of Bronzino as his court painter. She mentions that Cosimo de' Medici thought in terms of politics, geography, education, and economics. He did not, for example, import textiles; Cosimo "set up his own Florentine silk works" (p.10). And, she says, Bronzino "knew how to use art as a form of publicity"; as he painted Cosimo's consort, Eleonora de Toledo, he painted those very textiles perfectly (p. 10). Look:

What stays with you? The dress. The child's face is easy to love, in part, I think, because his clothing is so softly done. Eleonora's face has no chance up against those patterns, the shoulder laces, the enormous stylized flower on her chest. In Bronzino's defense, Rowland writes that perhaps Eleonora "seems less haughty than melancholy; she was probably already beginning to suffer from the consumption that eventually killed her" (p. 10). Her face is very far removed from the foreground, it seems to me; perhaps because she was ill. But we can imagine another version of this portrait, one where her face, pale and subtlety-done as it is, comes forward, where she is seen as a person who will soon not be here, and knows it, one where the dress fades into the distance because the person is what matters. Bronzino was more than skilled enough to create this other portrait, where the face is the thing ... and yet he chose the dress. I have sometimes thought that when artists paint these ruffles and laces so perfectly that they are adding to their resume, saying, "if I can paint these, I can paint anything." This seems more than a few lines on a resume... this may be the most civilized, and early form of ... dare I say it? ... advertisement, for the silks of Florence. They are lovely ...

And I have found a new painter who seduces with his brushed fabrics. Agnolo Bronzino, an extraordinarily talented Renaissance painter, lesser known than some of his contemporaries, has had two exhibitions devoted to him in the past year, one at the Palazzo Strozzi in Florence last winter and the other at the Metropoitan Museum of Art in new York last winter and spring. The catalogues are out, and there is a review by the very perceptive Ingrid Rowland in The New York Review of Books from May 26 (pages 8-10). It is a wonderful, thorough review; read it... it is really fine. She outlines the way he worked, his basing of some works on Michaelangelo's (and she reproduces a drawing as proof of this sculptural echo), and Cosimo de' Medici's choice of Bronzino as his court painter. She mentions that Cosimo de' Medici thought in terms of politics, geography, education, and economics. He did not, for example, import textiles; Cosimo "set up his own Florentine silk works" (p.10). And, she says, Bronzino "knew how to use art as a form of publicity"; as he painted Cosimo's consort, Eleonora de Toledo, he painted those very textiles perfectly (p. 10). Look:

What stays with you? The dress. The child's face is easy to love, in part, I think, because his clothing is so softly done. Eleonora's face has no chance up against those patterns, the shoulder laces, the enormous stylized flower on her chest. In Bronzino's defense, Rowland writes that perhaps Eleonora "seems less haughty than melancholy; she was probably already beginning to suffer from the consumption that eventually killed her" (p. 10). Her face is very far removed from the foreground, it seems to me; perhaps because she was ill. But we can imagine another version of this portrait, one where her face, pale and subtlety-done as it is, comes forward, where she is seen as a person who will soon not be here, and knows it, one where the dress fades into the distance because the person is what matters. Bronzino was more than skilled enough to create this other portrait, where the face is the thing ... and yet he chose the dress. I have sometimes thought that when artists paint these ruffles and laces so perfectly that they are adding to their resume, saying, "if I can paint these, I can paint anything." This seems more than a few lines on a resume... this may be the most civilized, and early form of ... dare I say it? ... advertisement, for the silks of Florence. They are lovely ...

Friday, May 20, 2011

"les chiens aboient, la caravane passe" / the dogs bark, the caravan passes

(which means, as the French would say, "let the world say what it will").

Virginia Woolf wrote (in A Room of One's Own, I think) that the world is filled with those who have "minded beyond reason the opinions of others." It is good to mind within reason, but too often, we artists do mind "beyond." So, with the French, I say les chiens aboient, la caravane passe.

I am joining in with the Art House Sketchbook Project 2012, because I will draw for it, and keep drawing, and I have begun to sketch each page from quotes or proverbs or idioms, as with this:

Virginia Woolf wrote (in A Room of One's Own, I think) that the world is filled with those who have "minded beyond reason the opinions of others." It is good to mind within reason, but too often, we artists do mind "beyond." So, with the French, I say les chiens aboient, la caravane passe.

I am joining in with the Art House Sketchbook Project 2012, because I will draw for it, and keep drawing, and I have begun to sketch each page from quotes or proverbs or idioms, as with this:

Thursday, May 19, 2011

figure and ground, ground and figure...Francis Bacon reversed

When we look at a Francis Bacon painting, such as "Screaming Pope" (the affectionate term for his "Study After Velazquez's Portrait of Pope Innocent X" from 1953, among others, one of which is in the art collection at the Vatican), we see a figure moving, in vertical lines of repetitions of itself, in agony or ecstasy or a frenzied combination of both. Bacon seemed to see the person in his paintings, the figure, as the only element requiring movement, considerable movement, generally more approaching an agony than an ecstasy. He kept and annotated and ripped and tore and re-configured photographs that could inspire his work. The source photographs that survived him are barely-there, as in this photograph of his then-lover, George Dyer:

This is from the book Francis Bacon: A Terrible Beauty, a show curated at the Hugh Lane Gallery in Dublin by Barbara Dawson and Martin Harrison. It becomes a very different thing than a photograph ... it is already tormented, "changed utterly," as Yeats wrote. Bacon's portraits, diptychs, triptychs all reflect this concern to show the body as moved from both within and without, as in this (unfinished?) Untitled (Self-Portrait) of Bacon from 1991-1992, from the same book:

Look at the lines. There is a frantic, circular repetition to this sketch. The face is pretty intact, but the feeling that this piece conjures up, at least for me, is changing, busy, unsettled, anxious... Bacon chooses to let the figure move against a flat ground ... not just here, but most of the time.

So I ask myself, what if it were the other way around? What if the figure were still, and the ground moving? Because, as we move through the air, the air appears to move... we think of ourselves as intact. The struggles tend to remain inside. Bacon exposes them. But what if the air responded, instead? What if the surroundings were the sopurce of energy for the painting, and what was "background" comes to the "foreground"? Take the comparison of Rubens and Picasso from a few posts back (April 26) and block out the figures from each... what survives here?

In the Rubens, the lovely view out of the curtained window. it still seems to calm and distant, too much a reminder of its former status as... filler? In the Picasso, a great deal stays with us. Look at the energy of his "ground" as it becomes figural, here... look at the lovely slices of blue, nearly vibrating... The whited-out Demoiselles are pretty angular and bold, but they fight, now, for space and for the sense of movement offered by those slices of sky and curtain. He could have gone abstract. It was always an option.

This is from the book Francis Bacon: A Terrible Beauty, a show curated at the Hugh Lane Gallery in Dublin by Barbara Dawson and Martin Harrison. It becomes a very different thing than a photograph ... it is already tormented, "changed utterly," as Yeats wrote. Bacon's portraits, diptychs, triptychs all reflect this concern to show the body as moved from both within and without, as in this (unfinished?) Untitled (Self-Portrait) of Bacon from 1991-1992, from the same book:

Look at the lines. There is a frantic, circular repetition to this sketch. The face is pretty intact, but the feeling that this piece conjures up, at least for me, is changing, busy, unsettled, anxious... Bacon chooses to let the figure move against a flat ground ... not just here, but most of the time.

So I ask myself, what if it were the other way around? What if the figure were still, and the ground moving? Because, as we move through the air, the air appears to move... we think of ourselves as intact. The struggles tend to remain inside. Bacon exposes them. But what if the air responded, instead? What if the surroundings were the sopurce of energy for the painting, and what was "background" comes to the "foreground"? Take the comparison of Rubens and Picasso from a few posts back (April 26) and block out the figures from each... what survives here?

In the Rubens, the lovely view out of the curtained window. it still seems to calm and distant, too much a reminder of its former status as... filler? In the Picasso, a great deal stays with us. Look at the energy of his "ground" as it becomes figural, here... look at the lovely slices of blue, nearly vibrating... The whited-out Demoiselles are pretty angular and bold, but they fight, now, for space and for the sense of movement offered by those slices of sky and curtain. He could have gone abstract. It was always an option.

Wednesday, May 18, 2011

" ... Out of kindness comes redness

and out of rudeness comes rapid same question, out of an eye comes research, out of selection comes painful cattle ...." (from "A Box" from Objects, from Tender Buttons, by Gertrude Stein).

Can a sketch reveal Stein's thoughts, here? The actual sensory details in this passage are: "redness," an "eye," "selection" (perhaps, if it is a physical culling), and ... "cattle." Words having to do with behavior include "kindness," "rudeness," "question[ing]," "research," and (possibly) "selection." The only descriptive words are the red in "redness" and "painful." So the words that overlap in all the categories? "Selection," "redness," "painful." The pieces in Tender Buttons are sometimes about wanting things that are not accessible ... or things being no longer what they seem ... this process, in this short excerpt, is a painful, red, selection? I have drawn peaceful cattle on a hill. But that isn't what Stein had in mind....

Can a sketch reveal Stein's thoughts, here? The actual sensory details in this passage are: "redness," an "eye," "selection" (perhaps, if it is a physical culling), and ... "cattle." Words having to do with behavior include "kindness," "rudeness," "question[ing]," "research," and (possibly) "selection." The only descriptive words are the red in "redness" and "painful." So the words that overlap in all the categories? "Selection," "redness," "painful." The pieces in Tender Buttons are sometimes about wanting things that are not accessible ... or things being no longer what they seem ... this process, in this short excerpt, is a painful, red, selection? I have drawn peaceful cattle on a hill. But that isn't what Stein had in mind....

Tuesday, May 17, 2011

three oranges, no apples....

I am working on the painting that is working on me ... I took a photograph of its new paint from an angle:

And then, I was looking back at other photographs and I like the orange notes (especially up against the swirling blues of the sky) in this photo from a visit to our son and his girlfriend in Los Angeles:

And, last, comes a small hand-painted bowl from Istanbul, found on a visit to a new store called Ottoman Art in St. Helena (www.ottomanartlc.com) with amazing contrasts in a small space:

And then, I was looking back at other photographs and I like the orange notes (especially up against the swirling blues of the sky) in this photo from a visit to our son and his girlfriend in Los Angeles:

And, last, comes a small hand-painted bowl from Istanbul, found on a visit to a new store called Ottoman Art in St. Helena (www.ottomanartlc.com) with amazing contrasts in a small space:

Monday, May 16, 2011

Gertrude Stein says "It is not clarity that is desirable but force.

Clarity is of no importance because nobody listens and nobody knows what you mean no matter what you mean, nor how clearly you mean what you mean. But if you have vitality enough of knowing what you mean, somebody and sometime and sometimes a great many will have to realise that you know what you mean and so they will agree that you mean what you know, what you know you mean, which is as near as anybody can come to understanding any one."

from "Henry James," by Gertrude Stein, written in 1932-3

Stein is writing about, first, "clarity," by which she means, for instance, approaching writing a novel with the outline done, then writing with the trail for the reader well-lit and the ending clear. No matter how magnificent the writing is, or what points the writer may have intended to make, this kind of writing is, ultimately, forgettable, "nobody listens." It is, as Richard Foreman would say years later, the kind of art that puts readers or viewers to sleep, because they know what will happen (see my post from May 4, "find the heretofore un-mapped"). But, second, Stein writes about the kind of writing that she wishes to do, and does, (unless she is overwhelmed by audience... see my post from April 7, "artist, audience, performance"). This second kind of writing comes of "vitality" (and is met, she suggests, with "vitality" from the reader) because you know what you mean. That is, the expression comes from somewhere inside you, as you write, and, like Hemingway's "truest" writing, cannot be prescribed, pre-planned, does not describe, but keeps the writer, and the reader, in the present moment of reading. This is why it can be so important for us to hear Stein's work being read... because the sounds keep the reader feeling that she "mean[s] what" she "know[s]." The reader is not, then, de-coding Stein, but walking, as my poetry Professor Robert Weisberg said once about reading T.S. Eliot, around the poem [or the prose] as if it were a sculpture. Stein wants you to walk around the words, hearing them, staying awake, and be "as near as anybody can come to understanding any one." Which is, after all, at least part of the point....

The reason I am interested in the "force" of Stein's writing today is... a new exhibit at the San Francisco Contemporary Jewish Museum, called "Seeing Gertrude Stein: Five Stories." The show features Stein in her own world, the one of her own making, and it begins with Stein reading from her work "Picasso." It starts with her voice. And then it proceeds to her writing, her friends, to Alice B. Toklas, the life they created together in Paris and the countryside, and brings together art-work, first editions, photographs and videos that have never shared the same space. There is a wonderful photo of Stein in a Balmain velvet suit at his fashion show, and another one of Stein and Toklas, about 3 years into their relationship, tanned and laughing and dressed in matching flowered dresses. Go. See it. There will also be a show at SFMOMA opening later this week about the Steins....

Years ago, we went to see Stein's house in Bilignin. At the time, it was lived in, and the residents were not willing to take us indoors, but we did walk along the terraces, and see the views and the gardens. It was beautiful. Afterwards, we drove down to the road below and took a photo of the house (below) and remembered what we had read, once, about the way residents of the town loved her and sheltered her in World War II: one of them said "credit for her until hell freezes over."

from "Henry James," by Gertrude Stein, written in 1932-3

Stein is writing about, first, "clarity," by which she means, for instance, approaching writing a novel with the outline done, then writing with the trail for the reader well-lit and the ending clear. No matter how magnificent the writing is, or what points the writer may have intended to make, this kind of writing is, ultimately, forgettable, "nobody listens." It is, as Richard Foreman would say years later, the kind of art that puts readers or viewers to sleep, because they know what will happen (see my post from May 4, "find the heretofore un-mapped"). But, second, Stein writes about the kind of writing that she wishes to do, and does, (unless she is overwhelmed by audience... see my post from April 7, "artist, audience, performance"). This second kind of writing comes of "vitality" (and is met, she suggests, with "vitality" from the reader) because you know what you mean. That is, the expression comes from somewhere inside you, as you write, and, like Hemingway's "truest" writing, cannot be prescribed, pre-planned, does not describe, but keeps the writer, and the reader, in the present moment of reading. This is why it can be so important for us to hear Stein's work being read... because the sounds keep the reader feeling that she "mean[s] what" she "know[s]." The reader is not, then, de-coding Stein, but walking, as my poetry Professor Robert Weisberg said once about reading T.S. Eliot, around the poem [or the prose] as if it were a sculpture. Stein wants you to walk around the words, hearing them, staying awake, and be "as near as anybody can come to understanding any one." Which is, after all, at least part of the point....

The reason I am interested in the "force" of Stein's writing today is... a new exhibit at the San Francisco Contemporary Jewish Museum, called "Seeing Gertrude Stein: Five Stories." The show features Stein in her own world, the one of her own making, and it begins with Stein reading from her work "Picasso." It starts with her voice. And then it proceeds to her writing, her friends, to Alice B. Toklas, the life they created together in Paris and the countryside, and brings together art-work, first editions, photographs and videos that have never shared the same space. There is a wonderful photo of Stein in a Balmain velvet suit at his fashion show, and another one of Stein and Toklas, about 3 years into their relationship, tanned and laughing and dressed in matching flowered dresses. Go. See it. There will also be a show at SFMOMA opening later this week about the Steins....

Years ago, we went to see Stein's house in Bilignin. At the time, it was lived in, and the residents were not willing to take us indoors, but we did walk along the terraces, and see the views and the gardens. It was beautiful. Afterwards, we drove down to the road below and took a photo of the house (below) and remembered what we had read, once, about the way residents of the town loved her and sheltered her in World War II: one of them said "credit for her until hell freezes over."

Sunday, May 15, 2011

The Fayyum Portraits...

The eyes – somehow stylized, somehow completely each man or woman’s own – astonish, even in the dimmed light (of the quietest room) of the Getty Villa at Malibu (where a few of these pieces rest; others are scattered, or in the Louvre... or not yet found). Each face belongs to a Greek man or woman living in Roman Egypt; each gaze is confident, vibrant, direct and beautiful, the sitter accomplished and mature, dressed in his or her best, and yet ... both artist and sitter know that the final painting will be wrapped together with a funeral shroud. These are death masks, mostly egg tempera on wood, buried and later, the wooden portrait was separated from the body by -- thieves? The works contain cracks, an awkward pose here and there, the colors have likely faded, and yet, and yet ... look at them!

These are not kings, none of them Tutankamen, and yet there is majesty, here ... if you are near the Getty Villa, the Louvre, or any other collection, go and see them ... they have waited a long time.

Saturday, May 14, 2011

Friday, May 13, 2011

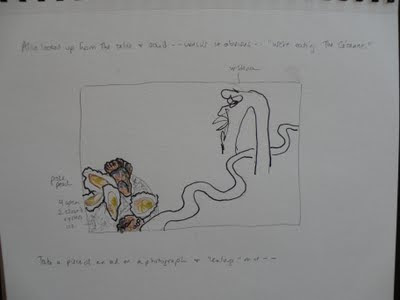

And Alice said -- wasn't it obvious -- "we're eating the Cezanne."

(when asked by a neighbor how they were faring in wartime... Alice B. Toklas and Gertrude Stein gestured to their reasonably lush plates of food....)

Wednesday, May 11, 2011

"Cubism has become a monument...."

In this corner, we have a close-up of a Cubist work by Pablo Picasso, from 1912: Violin, Glass and Pipe on Table. The painting (31 7/8" x 21 1/4" in the original) includes the classic elements, with stencilled letters, everyday objects with more than one side, as if we are walking around each one, the lines emanating from different horizons and centers, and, in a new move, some color (which would flex its muscles in the next few years):

There is no denying that this is a beautiful thing. It's the arrow shot from Cezanne's bow. But when you read Francoise Gilot (Life with Picasso) on her conversations with Picasso about Cubism ... she reports that he dismissed it as an important era in his art. Really. And she is VERY convincing on this point.

Not long after I first read her book, Picasso appeared to me in a dream. He said to me, in a tone that was urgent and agitated, that "Cubism has become a monument. It must not be a monument."

When Picasso stops by to converse, I always listen ... and try to determine what he meant. And so I turned to Gertrude Stein, who sat for her portrait with him (for 90 sittings) as he was turning from the harlequins to the Demoiselles. No-one converses with Stein and comes away unscathed, artistically. Stein would develop a distinction between what she called human nature/identity and the human mind/entity. Identity is pleasurable for the artist, and seems lovely at first, and results in art created for money or reputation, totally dependent on an audience (for whom the art-work or prose was very likely painted or written). But the real thing, entity, is art that is "not necessary," and is not based in memory or reproduction, but in writing "what it knows." That, she would say, is the real thing.

When I saw was confronted with Picasso's statement in my dream ... that monuments were not so wonderful, I aligned the monument idea with Stein's idea of identity. It is art made for reputation, money, audience. Or it is a great hulking piece of marble, remembering an event or a regiment. And so, it is sad, it is past, it is a label, it is fixed, it is finished. Here, someone was born, or celebrated a victory, or died. Monument. Art should have no truck with monuments. Picasso was telling me (or I was telling myself, as I slept) that Cubism was at first a series of exciting and bracing and unprecedented discoveries, with Braque, but then ... once it was "done," it was done. Like a Jackson Pollock, it gets imitators, but it is, itself, a done deal.

The part of the self that creates true art is Stein's entity. She mentions arches, the arches that were near St. Remy, as part of the land, as existing in the moment. Immersed. Creative. Not preserved in aspic, but mysterious. We struggle to keep up. And so I have this series of archways that are my response:

"Look, we have come through'"said D.H. Lawrence. An archway allows for this moment, for growth, for passage on to the next phase, for optimism in the face of fear, for art.

There is no denying that this is a beautiful thing. It's the arrow shot from Cezanne's bow. But when you read Francoise Gilot (Life with Picasso) on her conversations with Picasso about Cubism ... she reports that he dismissed it as an important era in his art. Really. And she is VERY convincing on this point.

Not long after I first read her book, Picasso appeared to me in a dream. He said to me, in a tone that was urgent and agitated, that "Cubism has become a monument. It must not be a monument."

When Picasso stops by to converse, I always listen ... and try to determine what he meant. And so I turned to Gertrude Stein, who sat for her portrait with him (for 90 sittings) as he was turning from the harlequins to the Demoiselles. No-one converses with Stein and comes away unscathed, artistically. Stein would develop a distinction between what she called human nature/identity and the human mind/entity. Identity is pleasurable for the artist, and seems lovely at first, and results in art created for money or reputation, totally dependent on an audience (for whom the art-work or prose was very likely painted or written). But the real thing, entity, is art that is "not necessary," and is not based in memory or reproduction, but in writing "what it knows." That, she would say, is the real thing.

When I saw was confronted with Picasso's statement in my dream ... that monuments were not so wonderful, I aligned the monument idea with Stein's idea of identity. It is art made for reputation, money, audience. Or it is a great hulking piece of marble, remembering an event or a regiment. And so, it is sad, it is past, it is a label, it is fixed, it is finished. Here, someone was born, or celebrated a victory, or died. Monument. Art should have no truck with monuments. Picasso was telling me (or I was telling myself, as I slept) that Cubism was at first a series of exciting and bracing and unprecedented discoveries, with Braque, but then ... once it was "done," it was done. Like a Jackson Pollock, it gets imitators, but it is, itself, a done deal.

The part of the self that creates true art is Stein's entity. She mentions arches, the arches that were near St. Remy, as part of the land, as existing in the moment. Immersed. Creative. Not preserved in aspic, but mysterious. We struggle to keep up. And so I have this series of archways that are my response:

"Look, we have come through'"said D.H. Lawrence. An archway allows for this moment, for growth, for passage on to the next phase, for optimism in the face of fear, for art.

Tuesday, May 10, 2011

"I want to ride to the ridge where the West commences...

And gaze at the moon until I lose my senses..." (from "Don't Fence Me In," written by Cole Porter, who went to Yale & Harvard Law School and lived in Paris, Venice, New York and Santa Monica, none of them places most cowboys traditionally roam... still, it is my favorite cowboy song).

My brother-in-law was visiting from Australia; he is an insanely talented painter and print-maker and is looking to return here to teach. While he was here, we three talked about: etching using zinc plates, painting at the kitchen table, his coming around to Matisse, diabetes, family, living alone, beaches, and we debated whether art should be taught as though the paths taken were as inevitable, and single-minded, as the unrolling of a long carpet, and we sang songs by Dan Hicks and the Lovin' Spoonful and Pure Prairie League (that would be "Amy, what you wanna do/ I think I could stay with you..."), the Allman Brothers ("Whippin' Post"), and any other song that echoed anything anyone said.

But, on our final night, when we had pretty much covered all the topics any reasonable person could expect to have considered... we found ourselves in a French restaurant in Berkeley. As we waited for the first course (flammenkuche to share and asparagus with pancetta and a poached egg) we started on lists: our best list, over the course of the night, was the 10 best Westerns of all time (in our humble opinion ... and the deal was, it had to be unanimous ... and the brothers were the most vocal ... just sayin'). The top 10 list, with no recourse to the web (we were in a lovely French restaurant, so here we go, un-checked), in no particular order:

open range

once upon a time in the west

hombre

the wild bunch

magnificent seven

the missouri breaks

red river

dances with wolves

left-handed gun

shane

And yours?

So, today, thinking over both rich sauces and cowboy movies ... I also cleaned up my storage areas:

and looked, yes, again, at the pear and river painting ... I have worked on it, yet something is wrong. So I have turned it upside down to find the spatial weaknesses ... "until I lose my senses..."

My brother-in-law was visiting from Australia; he is an insanely talented painter and print-maker and is looking to return here to teach. While he was here, we three talked about: etching using zinc plates, painting at the kitchen table, his coming around to Matisse, diabetes, family, living alone, beaches, and we debated whether art should be taught as though the paths taken were as inevitable, and single-minded, as the unrolling of a long carpet, and we sang songs by Dan Hicks and the Lovin' Spoonful and Pure Prairie League (that would be "Amy, what you wanna do/ I think I could stay with you..."), the Allman Brothers ("Whippin' Post"), and any other song that echoed anything anyone said.

But, on our final night, when we had pretty much covered all the topics any reasonable person could expect to have considered... we found ourselves in a French restaurant in Berkeley. As we waited for the first course (flammenkuche to share and asparagus with pancetta and a poached egg) we started on lists: our best list, over the course of the night, was the 10 best Westerns of all time (in our humble opinion ... and the deal was, it had to be unanimous ... and the brothers were the most vocal ... just sayin'). The top 10 list, with no recourse to the web (we were in a lovely French restaurant, so here we go, un-checked), in no particular order:

open range

once upon a time in the west

hombre

the wild bunch

magnificent seven

the missouri breaks

red river

dances with wolves

left-handed gun

shane

And yours?

So, today, thinking over both rich sauces and cowboy movies ... I also cleaned up my storage areas:

and looked, yes, again, at the pear and river painting ... I have worked on it, yet something is wrong. So I have turned it upside down to find the spatial weaknesses ... "until I lose my senses..."

Monday, May 9, 2011

the other side of the canvas....

Taking down and putting up and framing, today:

And more work on that painting ... the pear and the river ... and still there is either too much detail, or too little (it isn't clear to me yet):

The inspiration was a passage by W.G. Rogers, on traveling near Nimes with Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas: "Across a completely charming countryside where the air had the tang of ripening fruit, and where white, chalky soil burst in brilliant splashed through the vivid, sometimes dazzling, green of the foliage." You do see... you want some, but not too much, of that dazzle.

And more work on that painting ... the pear and the river ... and still there is either too much detail, or too little (it isn't clear to me yet):

The inspiration was a passage by W.G. Rogers, on traveling near Nimes with Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas: "Across a completely charming countryside where the air had the tang of ripening fruit, and where white, chalky soil burst in brilliant splashed through the vivid, sometimes dazzling, green of the foliage." You do see... you want some, but not too much, of that dazzle.

Sunday, May 8, 2011

peonies in a box, late, dying, a sign saying "5 STEMS -- $12.99"

as it unfolds

a white peony cracks

its bloom

peeling and twisting

to a brown edge...

from "In the Desert," by Charles Tarlton

a white peony cracks

its bloom

peeling and twisting

to a brown edge...

from "In the Desert," by Charles Tarlton

Saturday, May 7, 2011

" ... the omitted part ..."

I am working on the painting from yesterday and before ... (the pear is one piece of it), and I have been layering it so that the background and foreground are fighting with each other a bit:

Here, there is the slightest hint of a straight line up against the curve of the "river," but with the original boundaries softened a bit and the harsh colors gone ... Hemingway wrote, in The Moveable Feast, that he had not written the "real end" (which was a nasty one) of a story: "This was omitted on my new theory that you could omit anything if you knew that you omitted it and the omitted part would strengthen the story and make people feel something more than they understood." I love this idea ... [although when I talked about it with students in class, it took a lot of discussion before they understood or believed it!]. I think that when there is an idea that begins a painting, and then, as the painting goes along with the idea continually shifting shape, that if the idea sustains itself, then the painting can come into being. Here is another piece, and another after that:

Here, there is the slightest hint of a straight line up against the curve of the "river," but with the original boundaries softened a bit and the harsh colors gone ... Hemingway wrote, in The Moveable Feast, that he had not written the "real end" (which was a nasty one) of a story: "This was omitted on my new theory that you could omit anything if you knew that you omitted it and the omitted part would strengthen the story and make people feel something more than they understood." I love this idea ... [although when I talked about it with students in class, it took a lot of discussion before they understood or believed it!]. I think that when there is an idea that begins a painting, and then, as the painting goes along with the idea continually shifting shape, that if the idea sustains itself, then the painting can come into being. Here is another piece, and another after that:

Friday, May 6, 2011

"... The pears are not viols,

Nudes or bottles.

They resemble nothing else ....

The yellow glistens....

Citrons, oranges and greens

Flowering over the skin....

The pears are not seen

As the observer wills.

---from "Study of Two Pears," by Wallace Stevens

So much confidence in a pear. It is itself, except in Cezanne's hands, when it becomes his pear. Every apple, every pear, needs to shake itself free of Cezanne. Stevens's pears will not "resemble"; they will control the flow of their colors until the colors appear to blossom. These pears will never be eaten, because they are in a poem.

We think we see the outline of the pear -- but then, only then, afterwards, do we recognize the full pear. But, as Stevens also said, "The imagination does not add to reality." I think he means that the imagination can show us ... the seeing of reality ... we must seize this moment and this picture as we see it forming in our minds; paintings and poems come from this seizing of just this glistening of a pear.

(previous post, on April 28, showed a bit of pear ... and now here is my softer "pear," so far):

They resemble nothing else ....

The yellow glistens....

Citrons, oranges and greens

Flowering over the skin....

The pears are not seen

As the observer wills.

---from "Study of Two Pears," by Wallace Stevens

So much confidence in a pear. It is itself, except in Cezanne's hands, when it becomes his pear. Every apple, every pear, needs to shake itself free of Cezanne. Stevens's pears will not "resemble"; they will control the flow of their colors until the colors appear to blossom. These pears will never be eaten, because they are in a poem.

We think we see the outline of the pear -- but then, only then, afterwards, do we recognize the full pear. But, as Stevens also said, "The imagination does not add to reality." I think he means that the imagination can show us ... the seeing of reality ... we must seize this moment and this picture as we see it forming in our minds; paintings and poems come from this seizing of just this glistening of a pear.

(previous post, on April 28, showed a bit of pear ... and now here is my softer "pear," so far):

Thursday, May 5, 2011

The Queen's Skirt Explodes: silk vs. skin

I was looking at a series of paintings from 1994, a series I never exhibited. At the time, I was struck by a feature of most formal portraits that I have never seen anyone discuss at all. When Ingres painted the Princesse de Broglie in 1853, for example, he takes care with her face, and yet ... he takes far more care with her silk dress and bustle, and with the lace on her sleeves, even with the upholstery on the divan. I think that one could argue that this is proving one's worth as a painter; if you can paint a rounded, gleaming pearl, you can paint anything. It's something of an artist's resume, the velvet, the silk, the fur, the amethyst. But what of the face, when there is so much detail in the fabric and the jewels?

I began a group of paintings that would illustrate the problem ... the wealthy patron arrives for her portrait, and she is far less interesting to the artist than the usual model (think of Manet and Matisse, who painted the same woman repeatedly ... certainly because something about her particular presence would become significant in the final work). In the series, the Queen and the model ... clash. The model holds the artist's attention ... the Queen's skirt is actually the only thing keeping the painter looking in the Queen's direction. And so it goes ... here is the final work in the series, 38 x 50":

I began a group of paintings that would illustrate the problem ... the wealthy patron arrives for her portrait, and she is far less interesting to the artist than the usual model (think of Manet and Matisse, who painted the same woman repeatedly ... certainly because something about her particular presence would become significant in the final work). In the series, the Queen and the model ... clash. The model holds the artist's attention ... the Queen's skirt is actually the only thing keeping the painter looking in the Queen's direction. And so it goes ... here is the final work in the series, 38 x 50":

Wednesday, May 4, 2011

"... find the heretofore un-mapped," says Richard Foreman

On November 19, 1988, my husband and I saw a production at The Public Theater in New York that kept us talking for the full three-hour-drive home, and most of the next day, and for days and weeks after that. The play was What Did He See by Richard Foreman. We began to track down all of his writings; my husband was writing poetry and experimental dialogues and I was painting, and his complex ideas, we thought, needed to be felt, taken in, understood, and acted upon as we worked. In his "Ontological-Hysteric Manifesto I," Foreman talked about art and life and a thing he called "the scanning mechanism" which "produces art ... when its rhythms dominate the scanned object."

[I should note that, as far as I can remember, this was well before the words "scan" and "scanning" referred to anything with a tiny, pricey chip]. Instead, Foreman is talking about the way the mind and the senses of the artist look, then take in, and repeat the action, and take in again, and thus "dominate" what is seen by focusing, instead, on the process, its movement, and what it says about our creativity and ourselves. Art, he says, should "give courage to oneself and others to be alive from moment to moment, which means to accept both flux ... and an INTERSECTING process -- scanning -- which is the perpetual constituting and reconstituting of the self." Accepting change is one thing... Foreman wants us to seek change, flux, interchange, and in this way wake ourselves to what matters, to movement and art and to recognize "imbalance," which we "most deeply" are.

This follows, I think, from yesterday's post on Freud and "minor differences," which keep us both within civilization and aware of our "selves." We need "imbalance" -- even to pursue it if necessary --

because that working out of who we are against what we see is critical. Foreman says that art should expose us to "the true process of a certain kind of sentence-gesture (man's inner quest for style, for a way of being in the world) as it encounters the resistance of the real object (nature)." We see something, we imitate it, or draw it, or speak it, we "scan" it, and the natural object... is up against what we see, say, draw. It doesn't change. We do. The art shifts to explore this, and we live ... more fully.

He suggests, then, in a work called "How to Write a Play," that artists have a job: "find the heretofore un-mapped, un-notated crevices in the not-yet beautiful landscape ... and widen the gaps and plant the seed in those gaps and make those gaps flower ... and the plant over-runs the entire landscape." The thing that everyone draws, the thing that we always see, or respond to, the easy story, the thing we know ... those are not important in art and life, as we can sleep-walk our way through them. We want to find the things we have not yet seen, the hidden, the behind-things, the hints and "crevices" and we want to throw our lot in with all that we have not already known.

Richard Foreman has his own website, www.ontological.com, where he lists upcoming productions and opens his notebooks. Go look at it, and then tell me what you find there.... We still love his work.

Here is one of my old notebooks, and a manuscript that is clearly "in flux" --- and in need of planted seeds in its gaps. But it has value ... when I "scan" it, looking and repeating:

[I should note that, as far as I can remember, this was well before the words "scan" and "scanning" referred to anything with a tiny, pricey chip]. Instead, Foreman is talking about the way the mind and the senses of the artist look, then take in, and repeat the action, and take in again, and thus "dominate" what is seen by focusing, instead, on the process, its movement, and what it says about our creativity and ourselves. Art, he says, should "give courage to oneself and others to be alive from moment to moment, which means to accept both flux ... and an INTERSECTING process -- scanning -- which is the perpetual constituting and reconstituting of the self." Accepting change is one thing... Foreman wants us to seek change, flux, interchange, and in this way wake ourselves to what matters, to movement and art and to recognize "imbalance," which we "most deeply" are.

This follows, I think, from yesterday's post on Freud and "minor differences," which keep us both within civilization and aware of our "selves." We need "imbalance" -- even to pursue it if necessary --

because that working out of who we are against what we see is critical. Foreman says that art should expose us to "the true process of a certain kind of sentence-gesture (man's inner quest for style, for a way of being in the world) as it encounters the resistance of the real object (nature)." We see something, we imitate it, or draw it, or speak it, we "scan" it, and the natural object... is up against what we see, say, draw. It doesn't change. We do. The art shifts to explore this, and we live ... more fully.

He suggests, then, in a work called "How to Write a Play," that artists have a job: "find the heretofore un-mapped, un-notated crevices in the not-yet beautiful landscape ... and widen the gaps and plant the seed in those gaps and make those gaps flower ... and the plant over-runs the entire landscape." The thing that everyone draws, the thing that we always see, or respond to, the easy story, the thing we know ... those are not important in art and life, as we can sleep-walk our way through them. We want to find the things we have not yet seen, the hidden, the behind-things, the hints and "crevices" and we want to throw our lot in with all that we have not already known.

Richard Foreman has his own website, www.ontological.com, where he lists upcoming productions and opens his notebooks. Go look at it, and then tell me what you find there.... We still love his work.

Here is one of my old notebooks, and a manuscript that is clearly "in flux" --- and in need of planted seeds in its gaps. But it has value ... when I "scan" it, looking and repeating:

Tuesday, May 3, 2011

Image and text, part two: words are lines, too

... aren't they? Image and text are very closely related ... made of lines placed at precise intervals, the hand holding, perhaps, the same pen with the same grip, forming a letter or a blossom, a word or a horizon ... very much the same. And yet, Freud wrote, in Civilization and Its Discontents, that "it is precisely communities [or elements in a book or on a page, I would add] with adjoining territories, and related to each other in other ways as well, who are engaged in constant feuds and in ridiculing each other .... I gave this phenomenon the name of 'the narcissism of minor differences' .... We can now see that it is a convenient and realtively harmless satisfaction of the inclination to aggression, by means of which cohesion between the members of the community is made easier" (London: W.W. Norton, 1989, translated by James Strachey, p. 72).

It sounds as though admitting "same-ness" would actually diminish the possible cohesion within a group, because it might mean the loss of the individual, the self ... wait ... wouldn't that make it easier to bond? Well, Freud says no ... I think he is suggesting here that small, "harmless," controlled aggression can actually increase the thing that is equally "harmless," that bit of narcissism that allows us to feel ... just a bit different. No two soldiers or schoolchildren can ever be mistaken for one another, no matter how tailored the uniforms. In fact, the uniforms (like the similarities in the faces in that I mentioned on 4/26, the faces of the Amsterdam Musketeers) actually help us see the distinct expressions of a person's face. If we realize that people are, in these 'minor" ways, different, we ultimately come to respect them, I think.

So it must be with image and text. The "narcissism of minor differences" can enrich us. Since each is composed of lines, what lines can we draw between them? What lines within each reach out to the other?

It sounds as though admitting "same-ness" would actually diminish the possible cohesion within a group, because it might mean the loss of the individual, the self ... wait ... wouldn't that make it easier to bond? Well, Freud says no ... I think he is suggesting here that small, "harmless," controlled aggression can actually increase the thing that is equally "harmless," that bit of narcissism that allows us to feel ... just a bit different. No two soldiers or schoolchildren can ever be mistaken for one another, no matter how tailored the uniforms. In fact, the uniforms (like the similarities in the faces in that I mentioned on 4/26, the faces of the Amsterdam Musketeers) actually help us see the distinct expressions of a person's face. If we realize that people are, in these 'minor" ways, different, we ultimately come to respect them, I think.

So it must be with image and text. The "narcissism of minor differences" can enrich us. Since each is composed of lines, what lines can we draw between them? What lines within each reach out to the other?

Monday, May 2, 2011

"Drawing is Taking a Line for a Walk" Paul Klee; line and color

Yesterday's excellent Print Fair, at the San Jose Institute of Contemporary Art (SJICA), presented selected artists who make monotypes; it was a beautiful day and we had time to meet each other and see one another's (sometimes very different) styles of print-making.

When critics discuss painting, Matisse is often associated with color, and Picasso with line... I had not thought about this distinction in terms of print-making until yesterday's show at the SJICA. I could be slotted in under the "color" column:

... but other people whose work was on show yesterday would be ... taking lines for a walk. So it got me thinking, and looking at line. I took a Jasper Johns print (photogravure and collage) called "Untitled" (from 1986-2002) and drew it, rather loosely, just to see:

And then I drew some lilacs, imaging that they might be trying to fill the room:

It can be done! And Jasper Johns, incidentally, is a good role model for combining BOTH color and line....

When critics discuss painting, Matisse is often associated with color, and Picasso with line... I had not thought about this distinction in terms of print-making until yesterday's show at the SJICA. I could be slotted in under the "color" column:

... but other people whose work was on show yesterday would be ... taking lines for a walk. So it got me thinking, and looking at line. I took a Jasper Johns print (photogravure and collage) called "Untitled" (from 1986-2002) and drew it, rather loosely, just to see:

And then I drew some lilacs, imaging that they might be trying to fill the room:

It can be done! And Jasper Johns, incidentally, is a good role model for combining BOTH color and line....

Sunday, May 1, 2011

The perfect squirrel and the window, assignment from mid-April

I enrolled as an Art Education major when I first went to college. I didn't really understand what college could teach me about myself and about the world, and in the absence of any real understanding, I hoped to train for something. I took the first required drawing class in college. We had undergone the usual torture-by-still-life (those center-of-the-room assignments where we all drew a rocking chair, a teddy bear, a tinfoil star, a bit of plastic wrap, a leather-bound book, a light bulb, a mannequin's hand, a cereal box, whatever was smooth or rough or shiny or silky or transparent or fuzzy or wooden or weird... it was only a test, but it was every week).

I believe I was assuming I would learn draftsmanship (which is what it was still called then, in the dark ages). When we were given our fist real assignment, weeks into the term, which was (in its entirety) "draw a window," I was excited. I sought out the perfect one: a frame that had come loose from its moorings, a window-pane with a delicate crack, traces of scrubbed-away wallpaper. I succeeded, I was sure, in reproducing its 1910-or-thereabouts feeling. My charcoal-ed panes looked like real glass. I added a chair under the window. Looked like wood to me. I glued on some printed paper to help establish the remnants of wallpaper.

The critique was, then, going to be an event. We came rambling in, each of us push-pinning our final pieces up in a left-to-right row along the wall. I was feeling good; this was not a normal feeling for me, as I felt my fellow students were all, basically, Albrecht Durer on his best day.

Then SHE came in. She unrolled her drawing and pinned it up. Yes, it was a window, an old, wood-framed, slightly off-kilter window. But, more importantly, she was the only person in the class to have realized that it might be useful to allow the viewer to see something through the window. The rest of us had been so preoccupied with getting the glass right that we ignored the view. And her view was, it must be said, a perfect squirrel. Every little line of fur was distinct; there were shadows on his chest, there were gleaming eyes. To quote a Keats letter, "the creature hath a purpose, and his eyes are bright with it."

Not long after, I became an English major. And I earned another degree in English after that one.I made these decisions while thinking about the perfection of that student's drawing. But the fur, the eyes, the acorn between the squirrel's paws... none of that, in the long run, was important. What was important was that a window is to see through.

I believe I was assuming I would learn draftsmanship (which is what it was still called then, in the dark ages). When we were given our fist real assignment, weeks into the term, which was (in its entirety) "draw a window," I was excited. I sought out the perfect one: a frame that had come loose from its moorings, a window-pane with a delicate crack, traces of scrubbed-away wallpaper. I succeeded, I was sure, in reproducing its 1910-or-thereabouts feeling. My charcoal-ed panes looked like real glass. I added a chair under the window. Looked like wood to me. I glued on some printed paper to help establish the remnants of wallpaper.

The critique was, then, going to be an event. We came rambling in, each of us push-pinning our final pieces up in a left-to-right row along the wall. I was feeling good; this was not a normal feeling for me, as I felt my fellow students were all, basically, Albrecht Durer on his best day.

Then SHE came in. She unrolled her drawing and pinned it up. Yes, it was a window, an old, wood-framed, slightly off-kilter window. But, more importantly, she was the only person in the class to have realized that it might be useful to allow the viewer to see something through the window. The rest of us had been so preoccupied with getting the glass right that we ignored the view. And her view was, it must be said, a perfect squirrel. Every little line of fur was distinct; there were shadows on his chest, there were gleaming eyes. To quote a Keats letter, "the creature hath a purpose, and his eyes are bright with it."

Not long after, I became an English major. And I earned another degree in English after that one.I made these decisions while thinking about the perfection of that student's drawing. But the fur, the eyes, the acorn between the squirrel's paws... none of that, in the long run, was important. What was important was that a window is to see through.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)