We had a small earthquake last night ... about a 2.7 on the Richter Scale ... and we were upstairs, where we could really hear the little "boom" and feel the earth -- uncertain earth -- for just a moment. And it seems to me, as we have now had a few of these, that earthquakes are "feeling, then," AND "sound." Both. And so, to get myself away from worrying about earthquakes, I am thinking about Wallace Stevens and the poem where the line about "feeling" and "sound" shows up, "Peter Quince at the Clavier":

Music is feeling, then, not sound;

And thus it is that what I feel,

Here in this room, desiring you,

Thinking of your blue-shadowed silk,

Is music ....

Beauty is momentary in the mind --

The fitful tracing of a portal;

But in the flesh it is immortal ....

When I first read this poem, I wondered about that. Thinking about a thing makes it "real" and permanent -- gives it a place in the mind. But memory shifts, often because we will it to shift: Friedrich Nietzsche wrote "'I have done that,' says my memory. 'I cannot have done that,' says my pride, and remains adamant. At last -- memory yields" (an aphorism, from Beyond Good & Evil). So even a thought, a memory, disappears into another shape. So the live thing, the one we can hold, or hear, or see, or feel, that is the "immortal" thing. This may be why earthquakes, quite aside from the damage they can cause, are so scary -- because they can take up two senses at once, hearing and feeling.

So, in yet another attempt to escape these earthquakean ideas, I turn to paintings -- with music as subject. Here is a smooth-surfaced Caravaggio, "The Lute Player," from 1590:

The painter may have used a lens here for help -- David Hockney argues, in Secret Knowledge, that Caravaggio did use lenses in the 1590's -- just look at the photographic shadows and lighting here. Now, we skip ahead to a very different aesthetic, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, a detail from his "Christmas Carol" of 1867:

Is she playing? The strings here are of far less interest than her fingers (and eyes) ... Gustav Klimt was inspired by the final chorus of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony to paint this in 1902:

Here, the bodies and cloth and light is all reduced to beautiful patterns -- notes -- musical. The last painting is Matisse's "Music," from 1939:

The most musical, to me ... the eye is as engaged as the ear.

Friday, December 23, 2011

Wednesday, December 21, 2011

The Flâneur: Pissarro, Grimshaw, Vuillard

The flâneur -- the person who strolls, gazes, looks through the city streets for the life, the sights, and the sounds that are worth noting in an increasingly complex world -- seems an interesting idea to look into. I thought we could take a minute and think about the most revealing intersections, corners, windows, doors, outside spaces that I know, some I have been to and photographed

... like this enclosed garden that once belonged to Lawrence Durrell in a city somewhere in the South of France ... or this graffiti in (I think) Lyon:

But we can look farther out ... who looks at, and paints, outside scenes? Pissarro, for one, here a Paris Street/Montmartre scene, from 1877:

We can imagine walking in this rain, with the lights just coming on, people hurrying. I found a painting by John Atkinson Grimshaw, "Boar Lane, Leeds" from 1881:

Dusk, again, people heading out for drinks or home for dinner, and our flâneur just watching it all, detached, in no rush at all. Last, a lovely Vuillard, "Place Vintimille," from 1908-10:

It has the lovely rounded feeling of a fine Japanese screen. Where have you been that you'd like to paint just as if you were our flâneur?

... like this enclosed garden that once belonged to Lawrence Durrell in a city somewhere in the South of France ... or this graffiti in (I think) Lyon:

But we can look farther out ... who looks at, and paints, outside scenes? Pissarro, for one, here a Paris Street/Montmartre scene, from 1877:

It has the lovely rounded feeling of a fine Japanese screen. Where have you been that you'd like to paint just as if you were our flâneur?

Tuesday, December 20, 2011

Winter Moon Morning, and a new twist on two paintings....

This morning, the sky was a soft blue-pink, and the moon was still visible:

Really a nice, clean sense to the air today... So, I had been looking at a painting from an exhibition from 2 years ago...

Then I worked on the painting, adding colors... but it just would not come together. So I began sanding it down, and came up with "Female Gaze Uncovered in a Vineyard in Sonoma":

Really a nice, clean sense to the air today... So, I had been looking at a painting from an exhibition from 2 years ago...

It just didn't seem as strong to me anymore, so I whited it out and painted a new nude in outline, which I then transferred to the "Brushes" app and then I played:

Then I worked on the painting, adding colors... but it just would not come together. So I began sanding it down, and came up with "Female Gaze Uncovered in a Vineyard in Sonoma":

Sunday, December 18, 2011

"Pure Painting": pictures following Roberta Smith's eye, from Howard Hodgkin back to J.M.W. Turner

In a short review of Howard Hodgkin's show now at the Gagosian Gallery, Roberta Smith says that the work is "surprising" and "risky" (The New York Times, December 16, 2011, "Art In Review" section). But there is only a black-and-white photograph of one work -- not the one that interested me as I read the short essay by Smith. She mentions one work by Hodgkins in the show and proceeds to link it back to the "pure painting" of previous generations of painters. So I looked up the chain she mentions. Smith traces a line, first, from Hodgkin's "Breakfast" at the Gagosian:

back to an 1880 work by Manet. Manet had painted a bunch of asparagus for a collector and had expected 800 francs. The collector sent him 1000 francs, and Manet, delighted, sent him back a small single painted asparagus, saying, "there was one missing from your bunch." Here is "Asparagus":

Smith calls these examples of "pure painting" and gives us other names, like J.M.W. Turner. My choice for him is this "Snowstorm," from 1842:

I love Turner ... his landscapes, seas and clouds are filled with movement and allow us to perceive the world through abstract methods -- long before there was such a thing as abstract work. Smith also mentions Vuillard, someone whose work I do not know very well, so it was really fun for me to look through his work and find one that seemed to fit this "pure painting" idea. It is "Album," from 1895:

The figures meld into the wallpaper, creating a figure-ground movement, back and forth between the two. This makes it possible to gaze at the work for long periods of time -- this would be a likely way to define "pure painting," I would guess. Last, Roberta Smith mentions the Abstract Expressionists in this category, and of the first-generation painters, I would choose Kline as my "pure"-brushstroke man. Here is his "Untitled," from 1957:

This lovely small work is in the Philips Collection. People often think of Kline's work as only black and white, so I am deliberately picking this one to show you a work you might not have seen before.

That ends my tracing-through of Roberta Smith's examples; I have "illustrated" the article she wrote, just to see what all these paintings would look like together. Only two of the works, the Hodgkin and the Kline, are by painters considered to be fully abstract; the Turner, Manet and Vuillard are "abstract" only if we look at the brush-work. What links these five pieces as "pure paintings" is exactly that -- the tracings of movement by the artist's hand. (I have written about this "hors-catégorie" linking of Jasper Johns back to his "tribe" here on November 28).

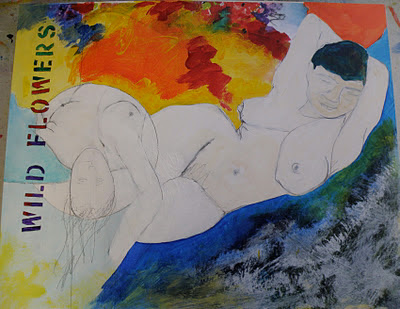

"Pure painting" here is demonstrably the brushstroke. It makes us want to "see," to look harder, to touch the original (which, of course, we can't do!!) or at least trace the line of the brush a few inches away in the air. Sometimes seeing a painting "live" for the first time is something of a shock. I had seen Picassos, for example, here and there in museums, but when I first went to the Picasso Museum in Paris, in 1989, seeing room after room of his work, the thing that surprised me was the relative flatness of his work, the absence, in so many cases, of obvious brushstrokes, and the way the painting tended to fade out towards its edges. I think that surprise was one of the origins for my "Odalisque" works -- imagining a more lively, brushed, colorful background for Picasso's 1907 "Demoiselles d'Avignon." Here is my "Les Demoiselles d'Avignon Pick Wildflowers" from 2010, where I take them out of Picasso's studio and give them some air:

So, as I am working now on the next few paintings in the series, I will be thinking of "pure painting."

back to an 1880 work by Manet. Manet had painted a bunch of asparagus for a collector and had expected 800 francs. The collector sent him 1000 francs, and Manet, delighted, sent him back a small single painted asparagus, saying, "there was one missing from your bunch." Here is "Asparagus":

Smith calls these examples of "pure painting" and gives us other names, like J.M.W. Turner. My choice for him is this "Snowstorm," from 1842:

I love Turner ... his landscapes, seas and clouds are filled with movement and allow us to perceive the world through abstract methods -- long before there was such a thing as abstract work. Smith also mentions Vuillard, someone whose work I do not know very well, so it was really fun for me to look through his work and find one that seemed to fit this "pure painting" idea. It is "Album," from 1895:

The figures meld into the wallpaper, creating a figure-ground movement, back and forth between the two. This makes it possible to gaze at the work for long periods of time -- this would be a likely way to define "pure painting," I would guess. Last, Roberta Smith mentions the Abstract Expressionists in this category, and of the first-generation painters, I would choose Kline as my "pure"-brushstroke man. Here is his "Untitled," from 1957:

That ends my tracing-through of Roberta Smith's examples; I have "illustrated" the article she wrote, just to see what all these paintings would look like together. Only two of the works, the Hodgkin and the Kline, are by painters considered to be fully abstract; the Turner, Manet and Vuillard are "abstract" only if we look at the brush-work. What links these five pieces as "pure paintings" is exactly that -- the tracings of movement by the artist's hand. (I have written about this "hors-catégorie" linking of Jasper Johns back to his "tribe" here on November 28).

"Pure painting" here is demonstrably the brushstroke. It makes us want to "see," to look harder, to touch the original (which, of course, we can't do!!) or at least trace the line of the brush a few inches away in the air. Sometimes seeing a painting "live" for the first time is something of a shock. I had seen Picassos, for example, here and there in museums, but when I first went to the Picasso Museum in Paris, in 1989, seeing room after room of his work, the thing that surprised me was the relative flatness of his work, the absence, in so many cases, of obvious brushstrokes, and the way the painting tended to fade out towards its edges. I think that surprise was one of the origins for my "Odalisque" works -- imagining a more lively, brushed, colorful background for Picasso's 1907 "Demoiselles d'Avignon." Here is my "Les Demoiselles d'Avignon Pick Wildflowers" from 2010, where I take them out of Picasso's studio and give them some air:

Friday, December 16, 2011

How Beautiful is the Surface of a Painting?: Jackson Pollock, Agnes Martin, Gerhard Richter

I am undergoing one of those struggles, whiting out the awkward, clumsy, thickly-uncertain brushstrokes in one of my paintings in the desire for smooth perfection. As I paint, I understand, completely I think, how it is that Agnes Martin wanted ruled lines, Gerhard Richter scrapes pure intense color, and Jackson Pollock danced. There is something perfect about melding geometric forms with "simple" color, as my circle does here:

Sometimes, I find myself wanting to know, "did that painter feel what I am feeling, painting? or was it only later that feeling entered in, looking at the finished work?"

So I decided to ask around. I started with Pollock, and "Number One," 1948:

So was this smoothness, this unity, always there in the making? In a review of the catalogue that accompanied the 1998 Pollock exhibition at MOMA, Claude Cernuschi discusses the two central essays, by Kirk Varnedoe and Pepe Karmel. Cernuschi says that Varnedoe calls for less theory, more "'close-order looking'" because " 'the whole story here is on the surface [and its] ... concrete, matter-of-fact presence' " (Archives of American Art Journal, Vol. 38, No. 3/4, 1998, p. 30). Cernuschi says that it might not be so easy, just looking, because "perception can never be pure" (34). I think, as much as I hate to admit it, that he is right: we are always coming to a painting with some pre-formed idea (ideal?) in our minds, some way of linking this work to our own knowledge, prejudices, experience. We certainly can't capture intention. Then, in Karmel's essay, Cernuschi tells us, Pollock is seen in a whole different light, not as a man of "surfaces" but as a painter interested in the "obfuscation-of-imagery," that there are outlines of figures under many of his works that he erases with his flowing lines, an argument corroborated by Lee Krasner. Cernuschi decides to bring the viewpoints together by linking Pollock with nature, abstraction with figuration, movement and resulting line...(37-8).

But when he does quote Pollock, check out what the painter says of his work: "it doesn't make much difference how the paint is put on as long as something has been said" (36). I think the something here is surface... look back at "Number One." The surface is undeniable ... even if we decide to bring in a few other observations, in my eyes, the surface trumps.

Then look at Agnes Martin. Her surfaces are utterly "plain" -- there are no hidden bodies here, certainly, and not paintings-over. She has said that she first saw each painting in her mind before she even started: "The struggle of existence is not my struggle .... Being outside that struggle I turn to perfection as I see it in my mind .... Although I do not represent it very well in my work, all seeing the work, being already familiar with the subject, are easily reminded of it" (Writings, p. 16). We all know perfection. Surface. ("Those Greeks," Nietszche says, "always stopping at the perfection of the surface" --rough paraphrase, from memory -- but I digress...). Here is Martin's "Wood 1" from 1963:

Perfect. Surface.

Then there's Gerhard Richter. Roberta Smith wrote that Richter's "quasi-Photo Realist images" have "a peculiar abstracting fuzz to their surfaces, while his abstract paintings, seemingly gestural as they are, always hint at the photographic. There's a sharp depictive quality to their dramatic brush strokes ... plus a complex palette ... the combined effect constantly keeps us guessing" (The New York Times, March 13, 1987, "Arts" section). Here is his "Courbet," from 1986:

I think it is those "combined effects" that makes us keep looking, even with all our baggage, at each of these painters, and, if I had to choose, I'd go for perfection.

So I decided to ask around. I started with Pollock, and "Number One," 1948:

But when he does quote Pollock, check out what the painter says of his work: "it doesn't make much difference how the paint is put on as long as something has been said" (36). I think the something here is surface... look back at "Number One." The surface is undeniable ... even if we decide to bring in a few other observations, in my eyes, the surface trumps.

Then look at Agnes Martin. Her surfaces are utterly "plain" -- there are no hidden bodies here, certainly, and not paintings-over. She has said that she first saw each painting in her mind before she even started: "The struggle of existence is not my struggle .... Being outside that struggle I turn to perfection as I see it in my mind .... Although I do not represent it very well in my work, all seeing the work, being already familiar with the subject, are easily reminded of it" (Writings, p. 16). We all know perfection. Surface. ("Those Greeks," Nietszche says, "always stopping at the perfection of the surface" --rough paraphrase, from memory -- but I digress...). Here is Martin's "Wood 1" from 1963:

Perfect. Surface.

Then there's Gerhard Richter. Roberta Smith wrote that Richter's "quasi-Photo Realist images" have "a peculiar abstracting fuzz to their surfaces, while his abstract paintings, seemingly gestural as they are, always hint at the photographic. There's a sharp depictive quality to their dramatic brush strokes ... plus a complex palette ... the combined effect constantly keeps us guessing" (The New York Times, March 13, 1987, "Arts" section). Here is his "Courbet," from 1986:

I think it is those "combined effects" that makes us keep looking, even with all our baggage, at each of these painters, and, if I had to choose, I'd go for perfection.

Wednesday, December 14, 2011

Ukiyo-e: "pictures of the floating, fleeting world ..."

French artists first became familiar with Japanese art at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1867. The characteristic subjects, the differences of scale, the unfamiliar intensities of color, and the innovations in the nature of background in these Japanese works soon found their way onto easels and sketchpads in the West. Here, just to remind ourselves what it must have looked like, at first, is a lovely print, "Irises," by Hokusai:

Look at the sharp edges of the leaves and the insect, the way the bottom does not feel heavy, but rather reaches upwards, and the ivory of the iris blossoms, though close to the color of the white-gray sky, are softly outlined and distinct.

What started me thinking about Japonisme? I recently saw a picture of a Renoir painting. Generally I think we see Renoir as a painter of sensuous women or small children immersed in gardens. Yet, here was this painting, "Still Life with Bouquet," from 1871:

Rembrandt (the framed work on the wall), Impressionism (the bouquet wrapped in white), the books and tablecloth (generic!) but then we see that vase and that fan ... they float. The influence is there. Then we look to Whistler, who has used Japanese styling in his landscapes and portraits ... but here is a beautiful little study, which appears to be called "The Blue and White Covered Urn" (really?):

Simple lines, elegant against the background, each mark with a slightly different shape, nothing repeated, all observed closely. Now to Van Gogh, who, again, is someone we know loved Japanese prints; here is his "Still Life with Japanese Vase with Roses and Anemones," from 1890:

Definitely not the still, calm world of the Whistler, and with a vase at an angle worthy of a Cézanne, here is energy -- tucked inside the Japanese envelope. And now to the latest of the artists in this group, Matisse, and his "Still Life with Apples on Pink Tablecloth," from 1924:

Here, Matisse has complicated the background, pulling the wall into the foreground just a bit, and he is taking chances, too, with the colors pink and yellow, which often tend to fight one another. Here, they seem to have just enough interaction to keep the eye moving around the canvas... and the blues here come from the traditional vase patterns that Whistler was studying but here they are given to us with a larger, freer brushstroke. Matisse would work in this mode pretty extensively ... but he seems to have been the only one of these artists to take the lessons of the Japanese print and apply them across his work.

And then I thought -- who else has looked at Hokusai and Horishige since the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries? There have been people here and there -- Brice Marden's "Cold Mountain" series, inspired by Japanese calligraphy, would be one contender -- but no movement, as such. And why not?

While we think about that -- why the excitement stopped with Matisse -- I did think of one painter who is working through her Japanese influences: Helen Frankenthaler. In a show at Knoedler & Co last winter, "East and Beyond," Frankenthaler exhibited work in the ukiyo-e tradition that she began in the 1980's. Here is one of my favorite works by Frankenthaler from this show, "For Hiroshige," a painting from 1981:

And here is another work, a woodcut, "Weeping Crabapple," from 2009:

These demonstrate, I think, the possibilities ... we have come full circle, but without losing anyone's own artistic "voice."

Look at the sharp edges of the leaves and the insect, the way the bottom does not feel heavy, but rather reaches upwards, and the ivory of the iris blossoms, though close to the color of the white-gray sky, are softly outlined and distinct.

What started me thinking about Japonisme? I recently saw a picture of a Renoir painting. Generally I think we see Renoir as a painter of sensuous women or small children immersed in gardens. Yet, here was this painting, "Still Life with Bouquet," from 1871:

Rembrandt (the framed work on the wall), Impressionism (the bouquet wrapped in white), the books and tablecloth (generic!) but then we see that vase and that fan ... they float. The influence is there. Then we look to Whistler, who has used Japanese styling in his landscapes and portraits ... but here is a beautiful little study, which appears to be called "The Blue and White Covered Urn" (really?):

Simple lines, elegant against the background, each mark with a slightly different shape, nothing repeated, all observed closely. Now to Van Gogh, who, again, is someone we know loved Japanese prints; here is his "Still Life with Japanese Vase with Roses and Anemones," from 1890:

Definitely not the still, calm world of the Whistler, and with a vase at an angle worthy of a Cézanne, here is energy -- tucked inside the Japanese envelope. And now to the latest of the artists in this group, Matisse, and his "Still Life with Apples on Pink Tablecloth," from 1924:

Here, Matisse has complicated the background, pulling the wall into the foreground just a bit, and he is taking chances, too, with the colors pink and yellow, which often tend to fight one another. Here, they seem to have just enough interaction to keep the eye moving around the canvas... and the blues here come from the traditional vase patterns that Whistler was studying but here they are given to us with a larger, freer brushstroke. Matisse would work in this mode pretty extensively ... but he seems to have been the only one of these artists to take the lessons of the Japanese print and apply them across his work.

And then I thought -- who else has looked at Hokusai and Horishige since the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries? There have been people here and there -- Brice Marden's "Cold Mountain" series, inspired by Japanese calligraphy, would be one contender -- but no movement, as such. And why not?

While we think about that -- why the excitement stopped with Matisse -- I did think of one painter who is working through her Japanese influences: Helen Frankenthaler. In a show at Knoedler & Co last winter, "East and Beyond," Frankenthaler exhibited work in the ukiyo-e tradition that she began in the 1980's. Here is one of my favorite works by Frankenthaler from this show, "For Hiroshige," a painting from 1981:

And here is another work, a woodcut, "Weeping Crabapple," from 2009:

These demonstrate, I think, the possibilities ... we have come full circle, but without losing anyone's own artistic "voice."

Tuesday, December 13, 2011

Van Gogh, Anonymous Nude, and Surrounding Air... and Lucian Freud

I started with this rather astonishing portrait of a woman by Van Gogh, from his stay in Paris in 1887:

and drew the outline of his nude onto a canvas, imagining the model away from her cramped Paris apartment, on holiday in a field of bright wildflowers in the Alps. Still, the body itself dominated the canvas, without anyone else there, and so I added two nudes from my own notebooks for company:

But now the painting seemed far too busy! So, I began to work through the painting, blanking out the added nudes and experimenting with my "brushes" app, so as not to disturb the actual painting too much:

Interesting, okay ... Now, back to thinking about the air around the women. The Van Gogh woman is powerful, but I want the surroundings, and the second nude, to carry their weight too. So here is a new version, so far:

I am thinking I still need to add "air" to the circle around the left nude ... today ... Lucian Freud also said that "the main point about painting is paint: that it is all about paint."

and drew the outline of his nude onto a canvas, imagining the model away from her cramped Paris apartment, on holiday in a field of bright wildflowers in the Alps. Still, the body itself dominated the canvas, without anyone else there, and so I added two nudes from my own notebooks for company:

But now the painting seemed far too busy! So, I began to work through the painting, blanking out the added nudes and experimenting with my "brushes" app, so as not to disturb the actual painting too much:

I am thinking I still need to add "air" to the circle around the left nude ... today ... Lucian Freud also said that "the main point about painting is paint: that it is all about paint."

Monday, December 12, 2011

"Create a ZONE in which placed things (head) luminate!" Richard Foreman said

The playwright and director Richard Foreman has also written several sets of "manifestos" along with his plays. I suspect he does this partly to explain his methods to himself, but we can overhear the conversation! My husband and I have seen his plays in New York, and we talk about his ideas all the time (I wrote about him here on November 30 and September 29-- and a few other times before that). He is a powerful influence. We both --often -- re-read a copy of a set of his writings, inter-woven with scenes from Foreman's plays, that was published originally in the journal Performance in 1972, called "HOTEL CHINA: Part 1 & Part 2." Foreman believes, with Bertoldt Brecht and Gertrude Stein, that art -- theater -- often puts audiences into a kind of comfortable trance, because they identify with the characters who are onstage and wait for the dilemma to be resolved. Viewers should not be waiting, passively, for the linear progression of introduction-problem-resolution; they should be awake to "the new possibility ... a subtle insertion between logic and accident, which keeps the mind alive." The play needs to be interrupted: "The field of the play is distorted by the objects within the play, so that each object distorts each other object and the mental pre-set is excluded" (p. 4).

In order to make this happen on his stages, Foreman has used all sorts of props and bizarre costumes; here is a scene from "What to Wear" in 2006:

Art: not concerned with essence

But with THING

used in such a way

that it vanishes

& what is

left is suspension:

In life. -------> . thing is tool --we get

somewhere.

In art. <---------> never get there

Suspended.

Why? Create a ZONE

in which placed

things (head) luminate!

Above, a shot from "Idiot Savant," 2009. (You can see more by Foreman on his website, www.ontological.com).

Why Foreman today, here, now? We went to the Open Studios in the Arsenal in Benicia yesterday, and saw an artist there, Sharon Payne Bolton, whose work brings Richard Foreman's ideas to mind. Her exhibition space is wallpapered with washed-over maps and fragments of French notebooks, and the art works (see the white-framed piece below) share shelf space with books, lasts for making shoes, lenses, glass bottles filled with vacuum radio tubes, rulers. The works themselves hold keys, or locks, or French papers from the 19th century (Bolton lived in France for a time) or small mechanical devices or waxed photographs:

We talked to Bolton about her similarities to Foreman, a writer she did not know, and about the ways her work can resonate with a viewer, because it is familiar, but not familiar, simultaneously. Her works are beautifully made (Bolton was a cabinetmaker, and her space is called "Cabinet of Curiosity"):

Each piece rewards continued scrutiny -- and holds the viewer in the present moment. Sharon Payne Bolton has created her own little world in each of her artworks:

If you can visit, do! If not, here is the artist's website: www.sharonpaynebolton.com

In order to make this happen on his stages, Foreman has used all sorts of props and bizarre costumes; here is a scene from "What to Wear" in 2006:

There might be strings between the stage and the audience, or a plastic wall, characters might stop, mid-sentence, to wind up a huge crank or sing three bars of a song. The story? We are not watching for story. We are watching for movement, for surprise, for what is happening right this minute. Foreman wrote that the audience must "Be happy NOT knowing in condition of wanting to know. Be joyous in that tension" (p. 18). He says, on page 5:

Art: not concerned with essence

But with THING

used in such a way

that it vanishes

& what is

left is suspension:

In life. -------> . thing is tool --we get

somewhere.

In art. <---------> never get there

Suspended.

Why? Create a ZONE

in which placed

things (head) luminate!

Why Foreman today, here, now? We went to the Open Studios in the Arsenal in Benicia yesterday, and saw an artist there, Sharon Payne Bolton, whose work brings Richard Foreman's ideas to mind. Her exhibition space is wallpapered with washed-over maps and fragments of French notebooks, and the art works (see the white-framed piece below) share shelf space with books, lasts for making shoes, lenses, glass bottles filled with vacuum radio tubes, rulers. The works themselves hold keys, or locks, or French papers from the 19th century (Bolton lived in France for a time) or small mechanical devices or waxed photographs:

We talked to Bolton about her similarities to Foreman, a writer she did not know, and about the ways her work can resonate with a viewer, because it is familiar, but not familiar, simultaneously. Her works are beautifully made (Bolton was a cabinetmaker, and her space is called "Cabinet of Curiosity"):

Each piece rewards continued scrutiny -- and holds the viewer in the present moment. Sharon Payne Bolton has created her own little world in each of her artworks:

If you can visit, do! If not, here is the artist's website: www.sharonpaynebolton.com

Sunday, December 11, 2011

The Line of Inquiry and Paintings, Flowers and Flamenco: We Must Be In Benicia

We went to the Open Studios at Benicia and met some wonderful artists. I am finding that I really like to look at works that I find moving and find the line of influence: what other artists keep these contemporary painters company? Diane Williams, of the I An I Studio on Jackson Street, displayed several gorgeous and powerful large paintings. An early oil, once part of a fifteen-foot triptych, was filed with energy:

And, because of the way I see painting now, I thought immediately of John Singer Sargent's "El Jaleo." No, the Sargent isn't an abstract and it is horizontal, but take a look at the colors -- the deep blacks, the grays, the hints, here, of orange that explode in the piece by Williams -- and the mood:

The viewer's eye is carried through the painting along the same -- driving -- curves. The layers of shadow and foreground/background here, and the dancer and her band, form the same kinds of intricate relationships for us to study.

My husband's clear favorite -- of all of Diane Williams's work on show -- was this painting, which anchors a front wall of her studio space; she calls these forms "Chrysanthemums":

Stunning. And here, I love this painting, but I am torn trying to find the direct line to this breakthrough. When I think about other artists who have pursued these rounded bursts of color, I have two people in mind. The first is Joan Mitchell and "Sunflowers":

There is a kind of beauty-coming-right-off-the-canvas here, in all three of these works, that means we can keep looking. These paintings are filled with joy.

And, because of the way I see painting now, I thought immediately of John Singer Sargent's "El Jaleo." No, the Sargent isn't an abstract and it is horizontal, but take a look at the colors -- the deep blacks, the grays, the hints, here, of orange that explode in the piece by Williams -- and the mood:

The viewer's eye is carried through the painting along the same -- driving -- curves. The layers of shadow and foreground/background here, and the dancer and her band, form the same kinds of intricate relationships for us to study.

My husband's clear favorite -- of all of Diane Williams's work on show -- was this painting, which anchors a front wall of her studio space; she calls these forms "Chrysanthemums":

Stunning. And here, I love this painting, but I am torn trying to find the direct line to this breakthrough. When I think about other artists who have pursued these rounded bursts of color, I have two people in mind. The first is Joan Mitchell and "Sunflowers":

And the second is Cy Twombly's "Rose" series:

There is a kind of beauty-coming-right-off-the-canvas here, in all three of these works, that means we can keep looking. These paintings are filled with joy.

Saturday, December 10, 2011

Unfinished paintings, perhaps: "No vanity's displayed..."

W.B. Yeats wrote, in what must be his best book of poems, The Winding Stair, a poem called "Before The World Was Made," and here is its first stanza:

If I make the lashes dark

And the eyes more bright

And the lips more scarlet,

Or ask if all be right

From mirror after mirror,

No vanity's displayed:

I'm looking for the face I had

Before the world was made.

So I was rooting around in my folders filled with images from magazines and from my xeroxed drawings, and I found this wonderful picture, from a French magazine article on Ingres (from six? years ago?):

The "vide intérieur" of this portrait, (the "empty interior"), the caption on the lower left reads, echoes a passage from Flaubert's Sentimental Education. But I wasn't clever enough to save the name of this work. It is exhibited in Le Musée Ingres in Montauban, France. One of Ingres's assistants painted in the background, and Ingres started in on the outline and figure. The closest Ingres woman to this sketch, in pose and manner, is his "Madame Moitessier," from 1856:

Wow. Here, there are no draperies, no distractions. The face here is more "finished" than Madame's, I would argue; you can see the model clearly, here. The third arm here will help Ingres make a decision about where to place the arms on the woman on the far right border of his 1862 "Turkish Bath":

We can see that he made his decision ... her head is framed by her arms. Ingres was 82 when he painted this scene. But the face of the (formerly three-armed) woman on the right is less complex and compelling than the "sketch" above...

I went to Picasso, next, who knew Ingres's work well; here is his "The Artist and His Model," from 1914:

This is a work emerging from Cubism ... Picasso had completed his best works in that mode by this point ... and we can almost feel the uncertainty here. "What now?"the artist, and the painting, seem to be asking. The unfinished work is playing figure against ground, the lines of an Ingres portrait against a less well-defined landscape ... because it is so open, so much a question, I find it fascinating.

One more, this from De Kooning, his "Seated Woman" of 1940, a "portrait" of Elaine, who would marry him three years later. De Kooning's "Women" have divided critics. I think they all descend from this sketch ... it feels, to me, just a bit unfinished ... and the beauty here appears and disappears, like the Ingres face in the mirror so many years before:

Matisse-ian, no? The fore-grounding of the figure here is clear, and yet... the powerful blues and oranges tend to overwhelm the body. De Kooning seems to be looking for Elaine's face, still. On November 5, I had written that if we can see that the artist is still looking, the work feels unfinished ... here, I think, that is true. "I'm looking for the face ... [she] had/ Before the world was made."

If I make the lashes dark

And the eyes more bright

And the lips more scarlet,

Or ask if all be right

From mirror after mirror,

No vanity's displayed:

I'm looking for the face I had

Before the world was made.

So I was rooting around in my folders filled with images from magazines and from my xeroxed drawings, and I found this wonderful picture, from a French magazine article on Ingres (from six? years ago?):

The "vide intérieur" of this portrait, (the "empty interior"), the caption on the lower left reads, echoes a passage from Flaubert's Sentimental Education. But I wasn't clever enough to save the name of this work. It is exhibited in Le Musée Ingres in Montauban, France. One of Ingres's assistants painted in the background, and Ingres started in on the outline and figure. The closest Ingres woman to this sketch, in pose and manner, is his "Madame Moitessier," from 1856:

Ingres was not interested, initially, in painting a portrait, but here we are. I like the idea of the "vide intérieur" passing through to this finished version; Madame's face is perfect, but rather out-matched by her dress. If we look closely at the mirror image of her face, however, the less "finished" portrait, there is a kind of mystery (a mystery that Picasso's large faces would pick up on, years later). I love the mirror image here, and that's what made me think of the Yeats poem, of the woman looking in "mirror after mirror" for the face she had "before the world was made." I like the fact that the "world" of Ingres's portrait was not quite finished in that mirrored face ... not-quite-finished works appeal, because you can almost see the artist thinking. Take a look at this sketch, an Ingres work called "Woman with Three Arms," from 1859, three years after the portrait of Madame:

I went to Picasso, next, who knew Ingres's work well; here is his "The Artist and His Model," from 1914:

One more, this from De Kooning, his "Seated Woman" of 1940, a "portrait" of Elaine, who would marry him three years later. De Kooning's "Women" have divided critics. I think they all descend from this sketch ... it feels, to me, just a bit unfinished ... and the beauty here appears and disappears, like the Ingres face in the mirror so many years before:

Matisse-ian, no? The fore-grounding of the figure here is clear, and yet... the powerful blues and oranges tend to overwhelm the body. De Kooning seems to be looking for Elaine's face, still. On November 5, I had written that if we can see that the artist is still looking, the work feels unfinished ... here, I think, that is true. "I'm looking for the face ... [she] had/ Before the world was made."

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)