and here is another drawing, coming out of a dream:

Thursday, June 30, 2011

Wednesday, June 29, 2011

"I call it death-in-ife and life-in-death"

Yeats wrote, in his poem, Byzantium... The line kept running through my head as I drew this afternoon:

Tuesday, June 28, 2011

Sunday, June 26, 2011

Saturday, June 25, 2011

Two sketches, one "real" and one virtual....

The first picture, the "real" sketch, is a wet wash on paper that is clearly meant to remain dry... the virtual version below that comes from iPad Brushes. Both are working towards the next painting, in what I am thinking of as the "juxtaposition" series...

Friday, June 24, 2011

Silks up against grass ...

Here is a newer version of the painting, following the indications from yesterday's iPad sketch:

Will sleep on it...

Will sleep on it...

Thursday, June 23, 2011

la prochaine visite guidée (the next guided tour)

I took a photograph of the painting I am working on -- the one about juxtapositions, borrowing the standout shape from the other day's model and her long dress ("Silks up against grass," from the June 21 post) -- and sent it to my iPad, and worked on it there in the Brushes application. Here is the version from this morning's session; the digital scribbles are clear, here, in a way they won't be in "actual" paint:

So now, it's up to me to work this out in non-virtual form... coming soon...

So now, it's up to me to work this out in non-virtual form... coming soon...

Wednesday, June 22, 2011

Grids and Layers...

Rosalind Krauss is visiting ... via 2 of her books. I have a feeling she will be here for a long time, as she has a good deal to say.

In the first chapter of Originality, Krauss discusses grids (does the grid by each artist cut off -- or contain -- the world?), and reproduces work by Jasper Johns, Agnes Martin, Robert Ryman, Caspar David Friedrich, Odilon Redon, Piet Mondrian, and Joseph Cornell. I once attended a lecture by an artist who said that he always knew that when he was reading theory, the studio work was not going well; "fiction," he said, "means it's a go." But ... I like reading theory! Krauss's grids are everywhere for me at the moment; here is a screen in Essex, Connecticut:

Then the question of layers ... I read an article today by Simon Abrahams, who writes the blog at "Every Painter Paints Himself." The article discusses two paintings by Manet ("Le Déjeuner sur L'Herbe" and "Mlle. V in the Costume of an Espada"), centering on the question of the different picture planes, and the different types of brushwork in each work. Read the article; here is the short version: http://www.everypainterpaintshimself.com/essays/manets_le_dejeuner_and_mlle._v._simply_explained/ The article is of a piece with his website, which also, by the way, has a splendid gallery of images, arranged alphabetically by painter.

And here is a close-up of a layered work I am just starting:

In the first chapter of Originality, Krauss discusses grids (does the grid by each artist cut off -- or contain -- the world?), and reproduces work by Jasper Johns, Agnes Martin, Robert Ryman, Caspar David Friedrich, Odilon Redon, Piet Mondrian, and Joseph Cornell. I once attended a lecture by an artist who said that he always knew that when he was reading theory, the studio work was not going well; "fiction," he said, "means it's a go." But ... I like reading theory! Krauss's grids are everywhere for me at the moment; here is a screen in Essex, Connecticut:

Then the question of layers ... I read an article today by Simon Abrahams, who writes the blog at "Every Painter Paints Himself." The article discusses two paintings by Manet ("Le Déjeuner sur L'Herbe" and "Mlle. V in the Costume of an Espada"), centering on the question of the different picture planes, and the different types of brushwork in each work. Read the article; here is the short version: http://www.everypainterpaintshimself.com/essays/manets_le_dejeuner_and_mlle._v._simply_explained/ The article is of a piece with his website, which also, by the way, has a splendid gallery of images, arranged alphabetically by painter.

And here is a close-up of a layered work I am just starting:

Tuesday, June 21, 2011

Silks up against grass

I was struck by a photograph (Jean Patchett, photographed by Norman Parkinson) from 1950, a model, turning away from the camera. No-one sits this way, in a dress this elaborate, unless ... for art. Some words come to mind: incongruity, juxtaposition, here and there, yes and no, or, perhaps, a simple phrase: my love is like a red, red rose. Kenneth Burke said, in A Grammar of Motives, that "metaphor is a device for seeing something in terms of something else. It brings out the this-ness of that, or the that-ness of this."

This indoor, reflective, fabric-centered shot, which I have painted over, needed to be contrasted with a bit of still life, a bit of landscape, a bit of "that-ness." Here is a two-piece drawing, then:

This indoor, reflective, fabric-centered shot, which I have painted over, needed to be contrasted with a bit of still life, a bit of landscape, a bit of "that-ness." Here is a two-piece drawing, then:

Monday, June 20, 2011

"A crinkled paper makes a brilliant sound..."

said Wallace Stevens, beginning "Extracts from Addresses to the Academy of Fine Ideas." And I quote him because I have just destroyed a painting (see photo of the poor thing, below), so I will think now of the next one, as I remember that I have, instead of a good painting, at the very least made "a brilliant sound":

Sunday, June 19, 2011

on "Waiting for the Moon"

It's a lovely little film (that just happened to win the 1987 Sundance Grand Jury Prize for Drama) directed by Jill Godmilow about the lives of Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas. The booklet that comes with the movie traces down which scenes and people are fictional -- or have been toyed with -- and which bits of the story are facts. The film looks over a period of about three months in (roughly) 1936, with Stein and Toklas moving between Rue de Fleurus in Paris and their country house, in Bilignin. The women who play Stein and Toklas are tender and wonderful... Linda Hunt plays an agreeable (but buttoned-up) Toklas, and Linda Bassett a smiling, patient but rather private Stein. Both actors ease you into their portrayals and invite you into this very inventive, quirky, writer-and-editor's world. The film is for sale at the Contemporary Jewish Museum ("Seeing Gertrude Stein: Five Stories" is there until September 6). Definitely worth an evening! And we have, just for today, my photograph of the house in Bilignin, in the Department of the Ain, rented for all those years by Stein and Toklas, photographed from below:

And now, for "Waiting," a small Bilignin-inspired sketch:

And now, for "Waiting," a small Bilignin-inspired sketch:

Saturday, June 18, 2011

"Not known, because not looked for..."

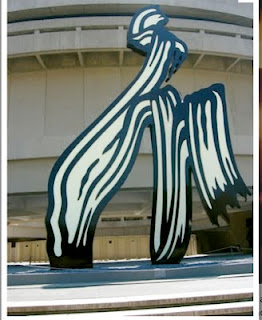

This is an enormous -- "brushstroke" -- sculpture in front of the Hirshhorn Museum of Art in Washington D.C.. As you know from my Benday Dot posts and drawings (March 7, 10, 12 and June 17), I really, really like Lichtenstein's work. Seurat, Monet and Picasso all presented us with the ways we see ... and Lichtenstein's work continues to expose the way we see as an illusion ... but, as with this brushstroke, an illusion we can be "in" on, and illusion we can enjoy, once we see it for what it is, as something that is both amusing and beautiful.

But Lichtenstein is criticized; just take a look at http://www.brooklynrail.org/2011/06/art/the-pleasures-of-art-peter-selz-with-jarrett-earnest And so, please, be sure to take a long, fair look at the work, not the work in reproduction ... see the artist's hand, the size of the original, the space it occupies...

Oh, and the quote in the title? from T.S. Eliot's "Little Gidding," The Four Quartets, and again

"Not known, because not looked for

But heard, half-heard, in the stillness

Between two waves of the sea..."

What do you think of Lichtenstein?

But Lichtenstein is criticized; just take a look at http://www.brooklynrail.org/2011/06/art/the-pleasures-of-art-peter-selz-with-jarrett-earnest And so, please, be sure to take a long, fair look at the work, not the work in reproduction ... see the artist's hand, the size of the original, the space it occupies...

Oh, and the quote in the title? from T.S. Eliot's "Little Gidding," The Four Quartets, and again

"Not known, because not looked for

But heard, half-heard, in the stillness

Between two waves of the sea..."

What do you think of Lichtenstein?

Friday, June 17, 2011

" ... tell why the glassy lights..."

Collaged draft of oyster, grid, girl, Queen's skirt, Benday Dot, Santa Fe... as I explained yesterday, maybe not an entire "inventory," but a reflection of what's on my mind today...

".... The lights in the fishing boats at anchor there,

As the night descended, tilting in the air,

Mastered the night and portioned out the sea,

Fixing emblazoned zones and fiery poles,

Arranging, deepening, enchanting night."

--from Wallace Stevens's "Idea of Order at Key West"

".... The lights in the fishing boats at anchor there,

As the night descended, tilting in the air,

Mastered the night and portioned out the sea,

Fixing emblazoned zones and fiery poles,

Arranging, deepening, enchanting night."

--from Wallace Stevens's "Idea of Order at Key West"

Thursday, June 16, 2011

In which the author has many things to say about...audience, the good and meaning

There was a young woman poet, C.S. Merrill, who worked for Georgia O'Keeffe in her final years, from 1973 to 1979, doing a bit of everything to help out (except art). She would sit down after each day and write what she and the artist discussed or did, and later published a book of poems, O'Keeffe: Days in a Life, (New Mexico: La Alameda Press, 2000). From these poetic notes, we find that O'Keeffe tended not to like her most popular paintings; she liked "a painting/with black V/white below/blue above" which was "what she was trying/to do." But it wasn't in the desired style -- so it was not going to be famous. Georgia O'Keeffe overly concerned about audience? At odds with what they wanted? She, the woman who said "I am not fine..."!!! How astonishing!

Then comes a poem that gets to a central difficulty artists have, making the judgment: "Is it finished? Is it good?" When I think I have done all I can with a painting, and am painfully aware of all the decisions I have made, all the work I have done to complete it, and remember the other destroyed paintings in its wake, I think, "this is a good painting." Since it is so easy for me to talk to myself and agree with what I have said, I have had to develop a system: if Charley and I both like it, then it is good. O'Keeffe settled that; she had an African mask "oval and black with protruding mouth/and slitty eyes; long braid/extending up from the head:

She used to take it with her summers

hang a painting next to it --

if it held its own

the painting was good,

next to the mask. (from "68," January, 1978)

And so it was good.

Turning back to Rosalind Krauss and Rauschenberg, Krauss unpacks the ways that he was changing the audience's expectations: how, after so many modern movements, to find meaning. Krauss refers to Renaissance art, to that little tiny landscape, tucked just over the Virgin's ear in so many Annunciation paintings, the little world going about its quiet little business just out of reach of miracles. She says this kind of painting portrays "a tunnel of deep perspective -- an allee of trees, say" which is "just about to arrive at its destination in the horizon's vanishing point, when something at the very forefront of the picture -- the lily the angel of the Annunciation is handing to the Virgin, for example -- blocks the whoosh into depth." So you have, on the one hand, this little distant world that is beautifully fixed in illusionistic space, in miniature, but then you are brought back to the flat faces of Mary and the angel and the world of the icon and halo. The moment in the foreground, Krauss says, must "'hold' the surface, preventing its 'violation by an unimpeded spatial rush.'" And, generally, it does, even though we see the "two conflicting modes of being ... real versus ideal, secular versus sacred, physical versus iconic, deep versus flat" and the funny thing is that it is that tiny real world back there behind the halo that is "real," and yet it is the one part of the painting that most makes use of illusion, perspective, the whole ball of wax. It is "the flattened wafer of the surface-bound icon that is touchably real" (p. 88, from "Perpetual Inventory" cited in yesterday's post). And so, if I am understanding her properly, what Krauss seems to suggest is that this dual nature of the picture plane requires us to perform the Keatsian suspension of disbelief and thus re-integrate the picture.

And, if I am getting that right, then I would suggest that the Keatsian moment and the re-integration, finding that meaning, is REALLY FUN for us as viewers and what can take the place of that exactly once you've broken it and you say you don't want anyone to put it back together? ... Yes, well, while Rauschenberg may have said, or hinted, that he didn't want it all put back together, he did, actually. Krauss quotes another critic, Brian O'Doherty, who says that Rauschenberg really was invested in "the integrity of the picture plane" (87). For me, Rauschenberg's most compelling work is the large photographic prints (there was a show recently in Los Angeles of several Gemini prints). Krauss discusses the "seamlessness" (95) he achieved with this breakthrough. And yet, for me, there is, along with the "seamlessness," an in-and-out quality not unlike that Renaissance duel.

So, again, as I did yesterday, I am going to say I will stop here and go work.... and buy an early Krauss book, because, clearly, when I read some of her pieces years ago, I wasn't ready.

Then comes a poem that gets to a central difficulty artists have, making the judgment: "Is it finished? Is it good?" When I think I have done all I can with a painting, and am painfully aware of all the decisions I have made, all the work I have done to complete it, and remember the other destroyed paintings in its wake, I think, "this is a good painting." Since it is so easy for me to talk to myself and agree with what I have said, I have had to develop a system: if Charley and I both like it, then it is good. O'Keeffe settled that; she had an African mask "oval and black with protruding mouth/and slitty eyes; long braid/extending up from the head:

She used to take it with her summers

hang a painting next to it --

if it held its own

the painting was good,

next to the mask. (from "68," January, 1978)

And so it was good.

Turning back to Rosalind Krauss and Rauschenberg, Krauss unpacks the ways that he was changing the audience's expectations: how, after so many modern movements, to find meaning. Krauss refers to Renaissance art, to that little tiny landscape, tucked just over the Virgin's ear in so many Annunciation paintings, the little world going about its quiet little business just out of reach of miracles. She says this kind of painting portrays "a tunnel of deep perspective -- an allee of trees, say" which is "just about to arrive at its destination in the horizon's vanishing point, when something at the very forefront of the picture -- the lily the angel of the Annunciation is handing to the Virgin, for example -- blocks the whoosh into depth." So you have, on the one hand, this little distant world that is beautifully fixed in illusionistic space, in miniature, but then you are brought back to the flat faces of Mary and the angel and the world of the icon and halo. The moment in the foreground, Krauss says, must "'hold' the surface, preventing its 'violation by an unimpeded spatial rush.'" And, generally, it does, even though we see the "two conflicting modes of being ... real versus ideal, secular versus sacred, physical versus iconic, deep versus flat" and the funny thing is that it is that tiny real world back there behind the halo that is "real," and yet it is the one part of the painting that most makes use of illusion, perspective, the whole ball of wax. It is "the flattened wafer of the surface-bound icon that is touchably real" (p. 88, from "Perpetual Inventory" cited in yesterday's post). And so, if I am understanding her properly, what Krauss seems to suggest is that this dual nature of the picture plane requires us to perform the Keatsian suspension of disbelief and thus re-integrate the picture.

And, if I am getting that right, then I would suggest that the Keatsian moment and the re-integration, finding that meaning, is REALLY FUN for us as viewers and what can take the place of that exactly once you've broken it and you say you don't want anyone to put it back together? ... Yes, well, while Rauschenberg may have said, or hinted, that he didn't want it all put back together, he did, actually. Krauss quotes another critic, Brian O'Doherty, who says that Rauschenberg really was invested in "the integrity of the picture plane" (87). For me, Rauschenberg's most compelling work is the large photographic prints (there was a show recently in Los Angeles of several Gemini prints). Krauss discusses the "seamlessness" (95) he achieved with this breakthrough. And yet, for me, there is, along with the "seamlessness," an in-and-out quality not unlike that Renaissance duel.

So, again, as I did yesterday, I am going to say I will stop here and go work.... and buy an early Krauss book, because, clearly, when I read some of her pieces years ago, I wasn't ready.

Wednesday, June 15, 2011

Shadowing Rosalind Krauss ... or is it Rauschenberg?

Rosalind Krauss begins her article "Perpetual Inventory" (October, Vol. 88, Spring 1999, pp. 86-116) with a headnote referring to its title, from a remark Robert Rauschenberg made to Barbara Rose: "I went in for my interview for this fantastic job .... The job had a great name -- I might use it for a painting -- 'Perpetual Inventory.'" And I immediately began to think that, yes, everything gets counted in ... and I thought, that's a really intriguing way to think of painting, as checking into the mind for what is important, how it presents itself in the imagination, what, then, it would be possible to re-present and then working onto canvas with a concerted effort. Later, speaking of Rauschenberg's photograph-laden silscreens in the early 60's, Krauss contrasts his approach, which is something of "a chance cut from the ongoing fabric of the whole world" with the art of a Renaissance painting, "a contraction around a gravitational center" (95). Voila. Brilliant.

So I thought that, for me, the two worlds could, instead of contrasting, converge. What if you had both a contraction and an explosion ... something like the Queen's Skirt series I have been thinking of ... the surface of the painting would be terribly active and the work itself a real challenge. So off I go.

So I thought that, for me, the two worlds could, instead of contrasting, converge. What if you had both a contraction and an explosion ... something like the Queen's Skirt series I have been thinking of ... the surface of the painting would be terribly active and the work itself a real challenge. So off I go.

Tuesday, June 14, 2011

Monday, June 13, 2011

A "crisis ... of a cognitive kind," the "imperfect" Paris, and a return of the oyster

I ran across a Harold Bloom quote, utterly irresistible because true: "a crisis, particularly of a cognitive kind, need be no more than a crossing point, a turning ... that takes you down a path that proves rather more your own than you would have anticipated." When that crisis comes, and it will, and it has, and it does ... you are no longer moored to anything you know ... that's when you find your way, even if it doesn't feel so "true" to begin with ... and Bloom goes on to say that "easier satisfaction" won't do it ... because there is "a more delayed and difficult reward" coming. "That difficulty," he says, is "an authentic mark of originality that must seem eccentric until it usurps psychic space and establishes itself as a fresh center" (from Ruin the Sacred Truths). Artists need to find that "fresh center." This is a beautiful affirmation of the taking of chances in life.

Bloom has written extensively about the poet Wallace Stevens, and I found a poem by him, today, as well, one I had not really "read" before, "The Poems of Our Climate." Looking at a bowl of red and white carnations, floating in a circle of water in a "low and round" bowl, "The day itself /Is simplified" but even that "world of clear water, brilliant-edged," is not enough ... "Still one would want more, one would need more," because we would come up against "the never-resting mind," and have to see that "The imperfect is our paradise." The simply beautiful becomes, even in the hands of an appreciative poet, "flawed words and stubborn sounds." Because, as Stein and Picasso agreed, as the artist creates that "path" or "fresh center" (that Bloom talks about), it will look "difficult" or "eccentric" or even, as Stein and Picasso said, that original work will look "ugly." Time will allow the audience to see it for what it is. Imitators may come along and make beautiful copies ... but the original will always be "imperfect."

And then there is Woody Allen, whose newest film, "Midnight in Paris," is simply wonderful. And it is about the perfect lure of Paris and its terribly "imperfect" present moment ... do see it.

And then there is the oyster. I am still working on the next drawing, so here is an oyster-rock, waiting:

Bloom has written extensively about the poet Wallace Stevens, and I found a poem by him, today, as well, one I had not really "read" before, "The Poems of Our Climate." Looking at a bowl of red and white carnations, floating in a circle of water in a "low and round" bowl, "The day itself /Is simplified" but even that "world of clear water, brilliant-edged," is not enough ... "Still one would want more, one would need more," because we would come up against "the never-resting mind," and have to see that "The imperfect is our paradise." The simply beautiful becomes, even in the hands of an appreciative poet, "flawed words and stubborn sounds." Because, as Stein and Picasso agreed, as the artist creates that "path" or "fresh center" (that Bloom talks about), it will look "difficult" or "eccentric" or even, as Stein and Picasso said, that original work will look "ugly." Time will allow the audience to see it for what it is. Imitators may come along and make beautiful copies ... but the original will always be "imperfect."

And then there is Woody Allen, whose newest film, "Midnight in Paris," is simply wonderful. And it is about the perfect lure of Paris and its terribly "imperfect" present moment ... do see it.

And then there is the oyster. I am still working on the next drawing, so here is an oyster-rock, waiting:

Sunday, June 12, 2011

Saturday, June 11, 2011

"you say 'ehr-stahs' and I say oysters..."

My parents always called an oyster an ehr-stah ... (from the lyrics to "Let's Call the Whole Thing Off" --- one of the best versions is Fred Astaire's). Here is my next version of the grid-oyster-lightning painting, to be continued ...

Friday, June 10, 2011

"Work engenders work."

Okay. Theoretically, I love this idea that I have been pursuing ... the idea of the Queen's skirt and the model. But I have made several sketches, now, and they are just not working for me. The drawings are messy where I don't want mess, and clean-lined when I want a little disorder; they are, in short, uncertain.

The Queen will need to sit in the studio a bit longer. Luckily, as Georgia O'Keeffe once said "Work engenders work" (or, it could be said, "work engenders better work"). Since I have been sketching and reading and gathering stones (you'll see) and looking out of windows, three things have turned up in the Queen's regal place:

1. I know I should have read this a very long time ago, but I just now finished Rosalind Krauss's original article, "The Originality of the Avant-Garde: A Postmodernist Repetition," (published in October, Vol. 18, Autumn, 1981, pp. 47-66). I won't try to summarize her argument, as she has published a book on the subject since this essay first appeared. She begins by reminding us that the avant-garde's claim to originality (and thus their whole reason for being) is their insistence on an "absolute distinction" between their world and "a tradition-laden past" (53). There is a piece of her argument concerning this search for the "new" that really interests me: her discussion of the grid. Krauss argues that the grid, the "new beginning" adopted by Mondrian, Josef Albers, and my hero Agnes Martin (see my entry from May 25th), isn't so "new"; Krauss calls it, to remind us of its long history, a "graph-paper ground" (54-6). The grid may seem to be "effective as a badge of freedom," and yet "it is extremely restrictive in the actual exercise of freedom" (56). It is vertical lines crossed by horizontal lines; it can, as Krauss says, "only be repeated" (56). She continues with the idea that originality and repetition are more "bound together" than we like to think, and that in seeking the original, we end up, well, repeating... (I had an idea, later, of an example of art-making that Krauss does not deal with in this article, though she may have gotten to it in the book... Robert Rauschenberg's erasing of the DeKooning drawing -- now in SFMOMA -- done with DeKooning's permission, is neither an original nor a repetition, and yet it is certainly avant-garde for its time... how to include that in the theory? And, then, there is Harold Bloom's Anxiety of Influence, where the strong poet must creatively misread his precursors -- not repeat or imitate -- and then erase all traces of the earlier poem, so that the new-generation poet's work will seem unique and yet -- written by the same hand as the earlier poem. Hmmm... ). But, finally, what stays with me, here, is the idea of the grid and its (new-to-me) "rut."

2. Hunting for rocks on a beach: I have found a set of rocks shaped like oysters, oyster-rocks:

And, here is a photograph of a recent dinner:

3. And, last, we had an insane thunder-and-lightning and wind-storm last night. The wind was scary ... it broke a window:

The lightning was a discovery: it would selectively light up first the house next door, then leap to a fence, then the distant sky, then the yard... so it seems those flashes of light must find their way into a painting.

So, here is the newest sketch. The oyster-rocks attack the grid, helped along by the occasional body (for added organic shape), and lit, from time to time, by boxes of lightning:

The Queen will need to sit in the studio a bit longer. Luckily, as Georgia O'Keeffe once said "Work engenders work" (or, it could be said, "work engenders better work"). Since I have been sketching and reading and gathering stones (you'll see) and looking out of windows, three things have turned up in the Queen's regal place:

1. I know I should have read this a very long time ago, but I just now finished Rosalind Krauss's original article, "The Originality of the Avant-Garde: A Postmodernist Repetition," (published in October, Vol. 18, Autumn, 1981, pp. 47-66). I won't try to summarize her argument, as she has published a book on the subject since this essay first appeared. She begins by reminding us that the avant-garde's claim to originality (and thus their whole reason for being) is their insistence on an "absolute distinction" between their world and "a tradition-laden past" (53). There is a piece of her argument concerning this search for the "new" that really interests me: her discussion of the grid. Krauss argues that the grid, the "new beginning" adopted by Mondrian, Josef Albers, and my hero Agnes Martin (see my entry from May 25th), isn't so "new"; Krauss calls it, to remind us of its long history, a "graph-paper ground" (54-6). The grid may seem to be "effective as a badge of freedom," and yet "it is extremely restrictive in the actual exercise of freedom" (56). It is vertical lines crossed by horizontal lines; it can, as Krauss says, "only be repeated" (56). She continues with the idea that originality and repetition are more "bound together" than we like to think, and that in seeking the original, we end up, well, repeating... (I had an idea, later, of an example of art-making that Krauss does not deal with in this article, though she may have gotten to it in the book... Robert Rauschenberg's erasing of the DeKooning drawing -- now in SFMOMA -- done with DeKooning's permission, is neither an original nor a repetition, and yet it is certainly avant-garde for its time... how to include that in the theory? And, then, there is Harold Bloom's Anxiety of Influence, where the strong poet must creatively misread his precursors -- not repeat or imitate -- and then erase all traces of the earlier poem, so that the new-generation poet's work will seem unique and yet -- written by the same hand as the earlier poem. Hmmm... ). But, finally, what stays with me, here, is the idea of the grid and its (new-to-me) "rut."

2. Hunting for rocks on a beach: I have found a set of rocks shaped like oysters, oyster-rocks:

And, here is a photograph of a recent dinner:

3. And, last, we had an insane thunder-and-lightning and wind-storm last night. The wind was scary ... it broke a window:

The lightning was a discovery: it would selectively light up first the house next door, then leap to a fence, then the distant sky, then the yard... so it seems those flashes of light must find their way into a painting.

So, here is the newest sketch. The oyster-rocks attack the grid, helped along by the occasional body (for added organic shape), and lit, from time to time, by boxes of lightning:

Thursday, June 9, 2011

Wednesday, June 8, 2011

Sketching the Queen's Skirt

A preliminary drawing ... more to come!

And here is the more ... too much, I think. (I like the simplicity of the original sketch better!).

Look at them both and see what you think!

And here is the more ... too much, I think. (I like the simplicity of the original sketch better!).

Look at them both and see what you think!

Tuesday, June 7, 2011

The Queen's Skirt Explodes, Part III, and Wendy Steiner and the Model

On May 5th and again on May 21, I talked about the ways that silks and satins and furs and jewels outshine the faces of Queens (and other elevated subjects, from Holbein to John Singer Sargent)... I had argued that one reason that we remember both a dress and an upholstered chair, but not always the expression of the supposed subject, from an Ingres painting, might be that the painter is displaying his talent: a well-painted pearl? ... another line on the resume. It could also be that the subjects themselves, from a higher class, unused to sitting so long, were not terribly forthcoming, and the painter became lost in all the decorative touches (every gorgeous thing the sitter owned, very likely) which actually spoke to him.

The Queen, in her sittings in the atelier, bored, would probably be noticing the painter's model (there was always a favorite); the Queen would, in her stiff pose, with her elaborate dress, be trying (consciously or not) to outshine the model, to keep the painter's attention on her royal personage alone. But the painter would be looking about, testing the light, seeing the familiar face, waiting, in the corner, and the model beckoned. I have always pictured this as a likely scenario, thinking that the model would be the dose of "real" life, something closer to the painter's own experience, that he would rather be attending to.

But I have been reading Wendy Steiner's book, The Real Real Thing: The Model in the Mirror of Art (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010), and she discusses a short story by Henry James, "The Real Thing." A couple, the Monarchs (hmmm... Queen and King?) press the artist-narrator to engage them as models, as his wife, for example, is so lovely, and Steiner says "This is just the trouble ... for Mrs. Monarch is already an artistic cliche, and the artist seems unable to make any art based on her that is not equally unoriginal" (page 38). And yet, when the artist considers his model, he sees that she is "'so little in herself'" and yet she encourages his leap to "'alchemy in art'" (38). So I think I need to refine what I have been thinking, thanks to Steiner's interpetation of the story.

It isn't exactly that the model represents the "real," or is somehow more real; it is that she, in what Steiner calls her "plasticity," can allow an artist to control the way she is represented, in a way that he cannot control the Queen's image.... He can create anything from his model. The Queen remains, stubbornly, herself. So, this is my new task for my next painting/drawing: a new Queen's skirt.

The Queen, in her sittings in the atelier, bored, would probably be noticing the painter's model (there was always a favorite); the Queen would, in her stiff pose, with her elaborate dress, be trying (consciously or not) to outshine the model, to keep the painter's attention on her royal personage alone. But the painter would be looking about, testing the light, seeing the familiar face, waiting, in the corner, and the model beckoned. I have always pictured this as a likely scenario, thinking that the model would be the dose of "real" life, something closer to the painter's own experience, that he would rather be attending to.

But I have been reading Wendy Steiner's book, The Real Real Thing: The Model in the Mirror of Art (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010), and she discusses a short story by Henry James, "The Real Thing." A couple, the Monarchs (hmmm... Queen and King?) press the artist-narrator to engage them as models, as his wife, for example, is so lovely, and Steiner says "This is just the trouble ... for Mrs. Monarch is already an artistic cliche, and the artist seems unable to make any art based on her that is not equally unoriginal" (page 38). And yet, when the artist considers his model, he sees that she is "'so little in herself'" and yet she encourages his leap to "'alchemy in art'" (38). So I think I need to refine what I have been thinking, thanks to Steiner's interpetation of the story.

It isn't exactly that the model represents the "real," or is somehow more real; it is that she, in what Steiner calls her "plasticity," can allow an artist to control the way she is represented, in a way that he cannot control the Queen's image.... He can create anything from his model. The Queen remains, stubbornly, herself. So, this is my new task for my next painting/drawing: a new Queen's skirt.

Monday, June 6, 2011

June 27, 1818

"I live in the eye; and my imagination, surpassed, is at rest ---" letter from John Keats. Today was such a day... the clouds on the East Coast are just different from West Coast clouds. Here, Rhode Island:

Sunday, June 5, 2011

Not "Seven Types of Ambiguity" but Three Types of Calligraphy, equal a drawing, and

" ... all drawing is collage," says David Hockney.

In 1816, Hokusai wrote, in his Album of Drawings in Three Styles, that he would like to bring together the three types of writing and ... drawing (mentioned, with examples from his work, Hokusai: Prints and Drawings, ed. Matthi Forrer, Prestel: Munich, 2010, discussion of figure 59). The three most common styles of Japanese writing, as I understand from my brief research on several sites today, are:

1. shin/kaisha: block characters, with clear shapes and structure

2. gyo/gyosho: where the points and lines of a character are connected, a near-cursive rendering,

rhythmic

3. sho/sosho: true cursive, sometimes called running, abbreviated, fast

The general progression from kaisha to gyosho to sosho is toward fluidity and abstraction. I shouldn't imply that any particular style is "best," however, because, as I read about him, I doubt Hokusai would say anything like that. I think he was trying to give lines in a drawing the same chance to be recognized and described as those in writing. So, I thought, the Hokusai book shows us his response; what about putting together three examples from other people?

So, for kaisha, I choose Ingres, "The Source":

There is some lovely fluidity in the portrayal of this body and the falling water; I am saying that this is like block or clear characters in writing because it is so crystal clear and clean of line. To demonstrate gyosho, or everything being connected, a Matisse, "Faith the Model," (this detail from the catalog The Steins Collect (plate 135), because it was purchased from Matisse by Sarah and Michael Stein, and this nude now lives in San Francisco):

There she is, completely moving into cursive, blending the colors of background and foreground, but still keeping recognizable form. For sosho, the style of writing that one source said might not even be readable to some people, I collaged and drew a form myself:

It is no longer as clear what is being "said" here ... and I would say that it is fully "cursive."

In 1816, Hokusai wrote, in his Album of Drawings in Three Styles, that he would like to bring together the three types of writing and ... drawing (mentioned, with examples from his work, Hokusai: Prints and Drawings, ed. Matthi Forrer, Prestel: Munich, 2010, discussion of figure 59). The three most common styles of Japanese writing, as I understand from my brief research on several sites today, are:

1. shin/kaisha: block characters, with clear shapes and structure

2. gyo/gyosho: where the points and lines of a character are connected, a near-cursive rendering,

rhythmic

3. sho/sosho: true cursive, sometimes called running, abbreviated, fast

The general progression from kaisha to gyosho to sosho is toward fluidity and abstraction. I shouldn't imply that any particular style is "best," however, because, as I read about him, I doubt Hokusai would say anything like that. I think he was trying to give lines in a drawing the same chance to be recognized and described as those in writing. So, I thought, the Hokusai book shows us his response; what about putting together three examples from other people?

So, for kaisha, I choose Ingres, "The Source":

There is some lovely fluidity in the portrayal of this body and the falling water; I am saying that this is like block or clear characters in writing because it is so crystal clear and clean of line. To demonstrate gyosho, or everything being connected, a Matisse, "Faith the Model," (this detail from the catalog The Steins Collect (plate 135), because it was purchased from Matisse by Sarah and Michael Stein, and this nude now lives in San Francisco):

There she is, completely moving into cursive, blending the colors of background and foreground, but still keeping recognizable form. For sosho, the style of writing that one source said might not even be readable to some people, I collaged and drew a form myself:

It is no longer as clear what is being "said" here ... and I would say that it is fully "cursive."

Saturday, June 4, 2011

"Cherchez La Femme"

.... means many things. The literal translation is "look for the woman," and the generally-understood meaning is that a woman is at the bottom of it all (she began it, she's to blame, she's the solution you seek...). This drawing comes from thinking that Picasso looked for a woman whenever ... he really needed to create a breakthrough work, like the Demoiselles. Below, my sketch of "her":

Friday, June 3, 2011

After yesterday, after Degas....

Yesterday, I had mentioned Degas's notebook and the note to "Cut things a lot .... No one has ever done monuments ... seen from low down, from beneath, close to, as one sees them passing on the streets." I said I would assign a trial drawing to myself. There is something about the sheer scale and majesty of the Temple of Dendur ... so I have tried to see that "cut" and "close to":

The next time I pass any kind of monument, I will look at it as Degas urged us to ...

The next time I pass any kind of monument, I will look at it as Degas urged us to ...

Thursday, June 2, 2011

Reprise of the "repoussoir"

On March 19, I had written about Hiroshige, the artists he inspired, and the close-up, the clipped edge, becoming, in a painting, a demonstration of time passing.... in his book, Mirror of the World (see my post from two days ago), Julian Bell also discusses the Hokusai and Hiroshige influences upon mid- to late-nineteenth-century European art. Bell calls this repoussoir "succinct" and 'witty" and quotes Edgar Degas's notebook: "Cut things a lot. For a dancer do either the arms or the legs .... Do all kinds of common objects, so arranged and contextualized that they have the life of men and women .... No-one has ever done monuments or houses seen from low down, from beneath, close to, as one see them passing in the streets." And Bell places Degas's memo to self next to a lovely work, "Place de La Concorde" (343).

I think these Degas-ian notes would make an excellent assignment for my next sketch. So I will work on that! But, in the meantime, I found two photographs and cropped them, and they do take on both a time-sense and the closeness of a human face, I think. The first is a newly-cropped close-up from the Canyon de Chelly, the second a cropped photo of a tree in Carmel-by-the-Sea:

I think these Degas-ian notes would make an excellent assignment for my next sketch. So I will work on that! But, in the meantime, I found two photographs and cropped them, and they do take on both a time-sense and the closeness of a human face, I think. The first is a newly-cropped close-up from the Canyon de Chelly, the second a cropped photo of a tree in Carmel-by-the-Sea:

Wednesday, June 1, 2011

Road-trip games and artistic hierarchies

So the game went like this: we each would be given one painting, only, to live with forever, can’t sell it, can’t trade it… so not necessarily your favorite painting, but the one you could look at … all the time. My husband’s is “The Piano Lesson,’ by Matisse, right now in the possession of MOMA New York.

Why? He says “It is representative painting just about to disappear like the Cheshire cat. The haunting little face – so ironic, that look, such a strange thing – is just about the only concession to realism. If that face (the Cheshire cat) should disappear, then what is left is a fabulous abstract-patterned painting, a Diebenkorn or a Hans Hoffman. One step beyond this painting is everything that follows, and one step beyond that? It would be one step beyond an e.e. cummings or Gertrude Stein poem, and then it would be like firing letters out of a shotgun … one step beyond their literature is total meaninglessness, because they are already doing abstract work. Second choice for the "forever" painting? Cy Twombly, because he is all about making the mark.”

Why? He says “It is representative painting just about to disappear like the Cheshire cat. The haunting little face – so ironic, that look, such a strange thing – is just about the only concession to realism. If that face (the Cheshire cat) should disappear, then what is left is a fabulous abstract-patterned painting, a Diebenkorn or a Hans Hoffman. One step beyond this painting is everything that follows, and one step beyond that? It would be one step beyond an e.e. cummings or Gertrude Stein poem, and then it would be like firing letters out of a shotgun … one step beyond their literature is total meaninglessness, because they are already doing abstract work. Second choice for the "forever" painting? Cy Twombly, because he is all about making the mark.”

For me: “The Demoiselles D’Avignon,” for many of the same reasons ... almost abstract, almost. It surprises me, that I didn’t choose an already-abstract work. And my second choice is even stranger, but I am sticking by it… “The Bar at the Folies-Bergere,” by Manet. So here I am, a confirmed non-representational artist, and I choose canonical works? So, okay, why these two? First, because I find them beautiful, and intriguing. I could easily look at them forever. So, yes, but there has to be something more.

So I am thinking, maybe what it is, is … a question of hierarchies. Thinking back, for the sake of brevity, just through the lines of Western art. Cave paintings, scratchings in the sand, then modest art for funerary purposes or literature, as with mummies or hieroglyphs, mythological illustration, then, more religious art (altarpieces, explanations of major events and stories) … and then patrons enter the picture, and things begin to change. A hierarchy is created, both for artists (within “school of…” and in competitions) and for works of art (an altarpiece pictures the conquering hero, the saintly donor’s face contemplated the Annunciation, the Night Watchers come forward out of the shadows). Religious or mythologically-themed paintings, historical portrayals (Washington, Napoleon) , even, a little further down in the list, a grandly-painted landscape showing the grandeur of England or France… but the still life? Not so much.

A pity, about the still-life, and its bottom-rung status. Because both Picasso and Manet were fabulous at still-life (we have all seen Picasso’s guitars and wine-bottles, but I was stunned when I first saw a series of Manet’s flowers – so beautiful!). But artists cannot make their reputation on a still-life or three, so each artist had to be thinking, what can I do? The age of Napoleon and the great altarpieces is past by 1883 and 1907, when my two chosen works were completed. What would be new enough? Picasso once said, lamenting that he was not Raphael, something along these lines: “since I cannot top the scale of hierarchies, I’ll destroy the scale.” Each of "my" two paintings, in its way, destroys the scale. Manet had already completed “Olympia” and “Dejeuner” (the modern woman in a classical setting), but now, with the woman in “Bar,” he pushes through the boundaries once more. This woman has no mythology, no religion, no great battles to justify her existence. Nothing backs her up … only a mirror. This may be one of the first truly modern paintings. It is she, alone, who must hold our attention. (And, simultaneously, the attention of the artist’s stand-in, her customer). She does. The painting works: the top of a new, grand, scale.

And Picasso would follow, years later, with his own bid for fame, although, as I have said before, I think he did not know what to do after that…

And Picasso would follow, years later, with his own bid for fame, although, as I have said before, I think he did not know what to do after that…

And the game is retired, for another day.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)