In her article "Jasper Johns:

This Is Not A Drawing" in

The Journal of Art (April 1991, pp. 16-17), Barbara Rose discusses Johns's drawings for the 1986 panels "The Seasons," which she says are his "first works to depict the human figure." She notes that Johns remembered seeing Cézanne's youthful murals, his "Seasons," preserved on his parents' dining room walls. The figures, writes Rose, are "poorly, laboriously, and unconvincingly drawn" and, "as if to mock his own ineptitude," they are signed "Ingres." Ingres, like Raphael, drew, without apparent effort, the most perfect continuous lines (David Hockney argues, in his book

Secret Knowledge, that lenses were involved for Ingres ... check his claims out). Rose tells us that Johns, in creating his own "Seasons," would face "the problem Cézanne devoted his life to solving: how to draw the contours of shapes without either flattening form into pattern or creating an illusion of space..." Rose then discusses the fact that many of Jasper Johns's critics have not looked at "The Seasons" in terms of "formal concerns .... as art." She believes that Johns, in "The Seasons," "faces head-on his major weakness as an artist," and says that critics should look into Johns's decisions here: "formal constructions ... how they deal with line, shape, space, et al."

So let's do that, shall we? Today, my husband visited several artists who participated in the Berkeley Open Studios weekend (continuing on weekends through the 18th of December -- and even the 24th in some cases). One artist, Nancy Fernandez, showed work that highlighted her exceptional drawing skills. She explained that she had studied in Florence, Italy, for three years, according to a classical system (followed from at least the nineteenth century onwards-- this was Picasso's course of study). Students begin by drawing casts, then progress to live models, all in pencil and charcoal, and may only move to colors when they have proven themselves worthy. Artists have -- always? -- copied the work of more established painters to learn how they made their decisions and, as Rose suggests, to see how works came to be "art."

So I was pretty surprised to read a critique by Jed Perl, written in 1996, about a group of late works by Jasper Johns, on display in the final room of the show "Jasper Johns: A Retrospective" at MOMA in 1996-7. Perl writes, in

Eyewitness: Reports from An Art Word in Crisis, that in these works completed in 1994, Johns merely "crops, edits, cuts and pastes" (147) from master works. And he goes on to say, "Any art student ought to know that a tracing of a painting isn't a response or an interpretation" and that the final pieces are dominated by rather "lackluster washes" (148). Okay, you are asking (unless you have scrolled ahead) -- what works did he copy -- what did his copies look like? I have to say that after reading this description by Perl (someone whose work I normally respect) I thought I would see a set of works displaying only a few bland outlines -- with a clear absence of effort and interest on the part of the artist.

I happen to have the catalogue for that retrospective, because we saw it in 1996. And then I flipped to the final images, and there were Johns's works: tracings of "Cézanne's Bathers" (1900-1905, 52 1/8" x 86 1/4") ... and, I have it on good authority, these were not tracings from a painting, but tracings of a

poster for a 1991 show in Philadelphia and Washington (that exhibited the "Bathers" from the Barnes Collection). So here I am thinking, before I really look at the photographs of the drawings, still, these will be silly ... from posters? tracings? Even though I knew that Johns owns a Cézanne himself, I thought, he has to be just playing. Here is the Cézanne that Johns owns, by the way, before we get to the original and its tracings: he owns "Bather with Outstretched Arms" (from 1877-8, Picasso, anyone?):

Cool, huh? Okay... I have delayed long enough. The original work that Johns traced, on plastic paper, six times that we know of -- the "Bathers":

There they are. There are a few of these "Bathers," but this is the one that struck Johns. I believe that he was continuing the work he began with his first painterly figures, "The Seasons," and giving himself his own version of a classical education. I am going to give you three of these "tracings," because I want you to see the variety of Johns's drawing and painting skills here. These are all called "Tracing After Cézanne," all ink on plastic, all from 1994. The first measures 18 1/8"x 30 3/8":

I think this is beautiful ... it catches the light and shadows and makes the most of the background, rather than the figures (a question I am very interested in right now), and also creates a kind of figure out of the right-hand tree. Here is the second that I like, which measures 18 1/8" x 28 3/8":

This creates a brown sheet or flag-like form in the center, a rooted tree or human outline in the lower left, a very delicate basket of food, and a happy explosion of tree limbs at top right. It adds much more light than the first tracing. Then, here is the third, which measures 18 x 28 1/8":

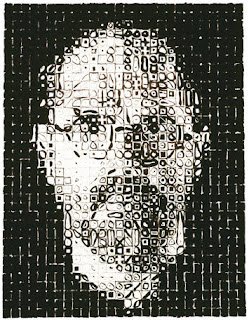

This is the final tracing. I love the way he has selected which lines to bring forward (the outlines of the center-right female and the woman just to the right of her arm) and the sky has really taken off here. I think we can say that Johns has entered the world of Cézanne, and, I would argue, the world of Ingres:

There is more detail in the hairline and along the bottom of noses and tops of lips, but, the forms and the sweep of the clothing, the setting of a mood, the hand of the artist? You decide. Are these in the same worlds, the world of art? I think they are.