A very young Robert Rauschenberg is perched high on a ladder

in front of a cathedral-style arched window, answering questions (undated

video, link posted at http://judys-journal.blogspot.com). We hardly hear the interviewer. Rauschenberg seems totally relaxed, and

really interested in describing his painterly approaches as accurately as

possible.

Let’s begin with his combine painting, “Rebus” (from 1955,

now at MOMA; photo below by Suzanne DeChillo for The New York Times):

Rauschenberg began with “a ground of newspapers … the

funnies …. I had an already-going surface, so there wouldn’t be a beginning to

the picture.” Now this is a very

interesting admission. The blank

canvas can be daunting, so I really like the idea of starting, as Rauschenberg

says, “an already-going surface.” (Rauschenberg is usually pretty articulate, so

the awkward structure of his phrase, “already-going,” seems particularly

telling –- it was deeply felt). Robert Motherwell had said that he started

paintings by making some kind of painted “gesture” on the canvas, and then, he

said, he would have a problem to solve.

Rauschenberg did not identify with Abstract Expressionists like

Motherwell, but he says, in this video, that what he did take away from their

“passion” was the fact that “they let their brushstrokes show.” But he also, tellingly, begins with a

“gesture.” For Motherwell it was a

sweeping brushstroke, for Rauschenberg it was “the funnies,” but the need for a

prompt is the same. We all need to

start somewhere.

After he confirms that “there wouldn’t be a beginning to the

picture,” because the funny papers had given him a starting point, he says this

very strange thing: “And so it

[would] all just be additive …. It doesn’t matter what’s inside.” I see what he means about the idea of

“additive,” that, given the newspaper ground, he just starts adding more

collage or paint or inks or wood.

But then what does he mean by “It doesn’t matter what’s inside”? “Inside” of what? He doesn’t mean inside his own mind

(because that does matter) or inside his plan for a painting (because there

isn’t one). I think he means that

it doesn’t matter what the bottom layer consists of, because it is “inside” the

finished combine. It may peek

through, but it is merely the starting point, and it is the accumulation of

stages that is important.

Rauschenberg continues, “it’s like when it stops because you’re dealing with an object, what it can make you think of how it could continue.

You begin with the possibilities

of the materials and then you let

them do what they can do.” Again, the language is rolling out and

he’s not policing it.

I am going to take some liberties here to try and see what

he is really saying. Rauschenberg

certainly never re-presented any objects in his work. He collaged photographs

of a Titian nude, or a rocket, or a street scene, but he never described an

object on a canvas with his own hand.

What he explains to us, here, is why. The flow of working “stops” for him when he thinks about “dealing with an object” on its own. If

he were, say, to try and work on a single “object,”

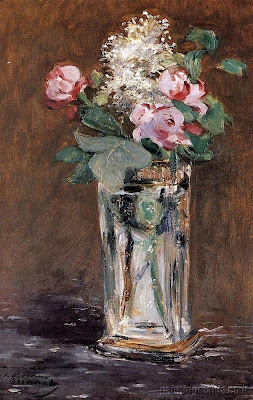

the way Manet has with his 1882 painting, “Flowers in a Crystal Vase”:

… it would all stop.

The initial gesture, the idea of adding elements to the combine or

painting, the flow of work would all be compromised, because of the necessity

of getting the vase and the water and the petals just so. And so there can’t be a hand-painted,

technically-perfect, light-and-shadows-following-the-curve object for him. When you land on an object, it lands

you.

And I know exactly what he means (assuming this is what he

means). When I was painting my

odalisque series, I was so worried about getting the outlines, getting the

form, getting the whiteness down right, as here, with “RIVER: Anonymous Odalisque

Reclines with Pillows” (3’ x 3’):

And I did love these paintings, but somehow the need to

paint them stopped. I thought of

them as exercises in freeing the odalisques, seeing them outside in a new

context, a beach, a riverbank. But

somehow they weren’t similarly freeing for me. And then my son said (not unkindly, but trying to help me

see why it wasn’t working for me anymore) “Well, there you are. A woman stuck

on wood.” And then I got it. That’s exactly right. The object “stops” the artist in his or her tracks. And that’s what Rauschenberg is saying.

We can’t, any of us, anymore, draw a vase filled with

flowers, the object re-pictured in its precise entirety on canvas. We can’t make the flowers out of wax

and armatures. But you can nail a

flower to 2 x 4. Early on in the

video, Rauschenberg gives us what may be his most important piece of

advice: “You have to work in the

hole between life and art,” he says, because “you can’t make either.”

Excellent post.

ReplyDeleteThank you, Judy, and thanks for the inspiration! I like to keep looking for that gap, between art and life.....

ReplyDeleteArtist In An A-Frame : "The Hole Between Art And Life": Robert Rauschenberg Unpacked >>>>> Download Now

ReplyDelete>>>>> Download Full

Artist In An A-Frame : "The Hole Between Art And Life": Robert Rauschenberg Unpacked >>>>> Download LINK

>>>>> Download Now

Artist In An A-Frame : "The Hole Between Art And Life": Robert Rauschenberg Unpacked >>>>> Download Full

>>>>> Download LINK